LINKING THE COMMUNITY AND

THE SHOOL: RAISING REVENUES LOCALLY

PART 3. EXPLORING LOCAL REVENUE OPTIONS

Under the current system, the State of California is the funding agent for

any increase in K-12 Proposition 98

revenues[17]. This places

significant added pressures on the state and has the effect of giving the

Capitol strong control over the delivery of educational services and programs.

Local control is whittled down to a limited form since local agencies are not

the funding agent for added revenues.

Under the current system, the state

raises and provides revenues for local education, and local school boards and

agencies make decisions on how to spend those revenues. This divided authority

muddles accountability. The state lawmaker must face the electorate for taxing

decisions while the local official can easily claim that “the state”

is not doing enough to meet minimum educational needs. Sometimes the conflict

becomes very visible: schools cry “foul” since they are dependent on

others for income, and state lawmakers cry “foul” when expenditure

decisions of local agencies do not match their vision of how education dollars

should be spent.

Finally, under the current system, any local

responsibility for adding optional education programs – and raising the

funds for those options – is lost. Local agencies do not have a realistic

opportunity to make decisions to increase local taxes for the addition of local

programs. There is no realistic option for a local agency to tax itself for

support of a local program. The accountability inherent in public

representatives raising taxes for public education and then standing for

election based on that decision is no longer available to California’s

school governing boards and communities.

As stated in the Framework

to Develop a Master Plan for Education, we share the belief that school

district governing boards can be more responsive to local educational needs and

priorities, and can be held more accountable by local electorates for

programmatic decisions, when they are able to generate revenues locally and can

demonstrate a direct connection between a revenue source and specific

educational services. The framework establishes the following parameters for

review:

This part of our report explores the viability of

local revenue options for school districts.

Historically, the ad valorem[18]

property tax was the single largest source of support for K-12 schools. In 1975,

property taxes accounted for more than two-thirds of all school district

revenues. Property tax rates were determined locally with voter approval.

Therefore, the communities of local school districts held significant discretion

over the amount of funding that would be made available to the schools through a

self-imposed property tax assessment. Local revenue raising authority was

matched by a local governance structure, with school boards elected by and from

the same communities that approved the level of fiscal effort in support of

their schools.

School finance equity litigation (Serrano) and a property

tax limitation initiative (Proposition 13) provided impetus for dramatic change

in the structure of school finance in California. The state responded by

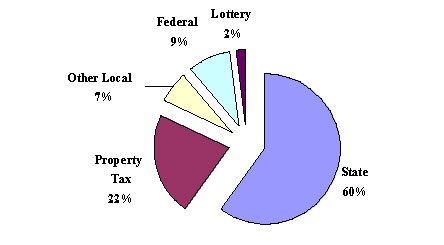

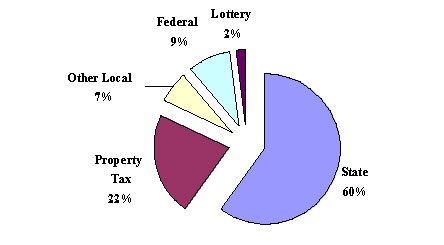

assuming responsibility for funding the schools, and, as chart 1 shows, state

resources came to provide the bulk of support for K-12 education.

Sources of revenue for K-12 education[19]

(Chart 1)

While nearly 30 percent of public school funding still comes from local

sources, K-12 schools now have very limited ability to raise revenues locally.

The bulk of “local” revenue in the current financing system comes

from the local property tax, and property tax revenues allocated to local school

districts are a dollar-for-dollar offset to state aid. In fact, in lean budget

years, property tax growth often accounts for the majority of new

“state” money provided for K-12 education programs. Finally,

property tax rates are set by constitutional and statutory provisions not

subject to local control.

Currently, school districts can receive locally

raised revenue through a few previously authorized special taxes. School

districts can, with approval of the electorate, impose a parcel tax and they can

participate in a local sales tax through a local public finance authority.

Schools raise funds locally through foundations and other parent-centered

fundraising. While these sources of revenue may be significant for some school

districts and schools, they are limited in their application across the

state.

There are many compelling reasons to once again establish meaningful local

revenue raising options for school districts:

It is critical to recognize that a meaningful local revenue option must link local revenues to those purposes that are best developed and resourced locally. In particular, we would caution that local revenues raised from an optional tax must not become a means of mitigating inadequate basic educational funding that is a statewide responsibility. Rather, revenues raised from a local option tax must be available wholly at local discretion to augment all other funds received for the educational program.

The working group identified specific criteria to assist it in evaluating four different local revenue options:

The working group has considered four local revenue options, and assessed

each against our evaluation criteria: The parcel tax, the sales tax, the ad

valorem property tax, and the income tax. We are recommending that the

Legislature consider three levels of commitment to local revenue options, each

corresponding to one of the three tax options we are

recommending[23]. The three levels

represent our assessment of the perceived or actual degree of change necessary

to implement our recommendations. The first option we present, a modification

to the parcel tax, represents what we believe would be a relatively small step

beyond current practice. The third and last option, amending the ad valorem

property tax, would require a change to constitutional and statutory provisions

adopted through Proposition 13, and so is likely to represent a much more

substantive change.

Since the enactment of Proposition 13, school districts have been

authorized to levy a parcel tax with approval of two-thirds of the voters.

However, the parcel tax is used in only a small number of school districts

– a total of 48 school districts (<1%) levied a parcel tax in 1998-99.

Moreover, a review of successful parcel tax elections shows that the parcel tax

has been approved primarily in school districts with higher income,

well-educated families. In those districts that have adopted parcel taxes, the

average revenue exceeds $500 per pupil. Districts with predominantly lower

income families tend to be less successful in gaining approval of parcel tax

proposals. [24]

In

successful districts, implementation of the parcel tax varies. In addition to a

single, fixed assessment per parcel, some districts have adopted parcel taxes

with differential rates for residential and commercial parcels (Davis Unified

School District). Other districts have adopted parcel taxes based on a

per-square-foot assessment (Berkeley and Albany unified school districts).

Specific exemptions, such as senior citizens, have been granted, and annual

automatic COLA adjustments have been provided. Most, but not all, parcel taxes

have a time limit, when the school district must return to the voters for

reauthorization. All parcel tax referendums state the purposes for which the

revenue may be used. Parcel tax revenues for a given assessment can vary among

communities, in that districts encompassing more parcels of land can raise more

revenue for a given parcel tax rate than other districts with fewer parcels.

Although in limited use now, we believe that the parcel tax may be among

the most viable local revenue options for school districts at this time, for the

following reasons:

Of the 128 parcel tax elections that

failed to achieve a two-thirds majority vote, 87 (68 percent) were approved by a

margin of 55 percent or better of the voting electorate. Recent electoral

support for local school facility bond measures based on a 55 percent threshold

lead us to believe that public support for schools is strong. Therefore, the

working group recommends that a Constitutional amendment be considered:

Recommendation 3.1:Approve a ballot initiative to reduce the voter approval threshold for parcel taxes from two-thirds to 55 percent. |

The sales and use tax (SUT) is the second largest tax levied in

California, with revenues totaling $32 billion annually. Levied at both the

state and local levels, three-fourths of the revenues accrue to the state and

one-fourth to local government. A component of the sales tax is a local option

levy, which causes sales tax rates to vary by county, ranging from 7 percent in

those counties with no local levy to a high of 8.25 percent.

California

has a high SUT rate when compared with other states, but because of its many

exemptions SUT revenues per $100 of personal income are slightly below the

national average. The SUT has been a reliable and stable tax with relatively

good growth. However, the SUT has represented a declining share of personal

income over the past 20 years, which may raise questions about its long-term

viability.[25]

The portion

of the SUT that can be levied at local option is used in just 24 of 58 counties.

Local option levies cannot exceed a total of 1.5 percent, and currently range

from 0.125 to 1.25 percent. They can be adopted by counties, cities and special

districts, for use to fund local programs in transportation, public libraries

and other services, including public education. The largest use of local option

SUT levies supports transportation projects. Our review shows the following

characteristics that support the sales tax as a local option for school

districts:

However, the sales tax also is less desirable for

several reasons:

Although a local option SUT levy can currently be proposed and approved for the benefit of public education, the process has not been conducive to widespread use by the schools. Therefore, we make the following recommendation so that schools can put directly to local voters a sales tax increment increase to support public education in their community.

Recommendation 3.2:

|

The ad valorem property tax accounts for nearly one-third of all tax

revenue accruing to local governmental agencies. Statewide, more than half of

property tax revenues are allocated to support K-12 schools, but the specific

percentage among counties varies widely across the state due to historical

differences in the local distribution of property taxes. Property tax

distributions among local governmental entities have been set by the state since

the voters approved Proposition 13 in 1978. This tax initiative severely limited

the ability of local governments to raise revenues through the property tax, by

(1) setting the countywide tax rate at no more than 1 percent of assessed

value[26]; (2) allowing local

reassessment of real property only upon resale, based on the sale price; and (3)

limiting annual growth in assessed value to 2 percent. In addition, as noted

earlier, the state response to Serrano incorporated local property tax

revenue to schools as a dollar-for-dollar offset to state general-purpose aid.

In essence, then, local property taxes are no longer subject to control by the

local electorate and the school's share of those taxes simply supplements

state-established per-pupil funding levels for the schools.

Nonetheless,

based on our evaluation criteria, the property tax arguably provides the best

source of local revenues for schools:

Since Proposition 13 established

its key provisions in the state Constitution, a Constitutional amendment would

be required if the property tax were to again become a viable option as a

discretionary local revenue source for schools. If the Joint Committee believes

that this option is politically viable, we recommend consideration of a proposed

Constitutional amendment:

Recommendation 3.3:

|

| Table of Contents | |||

| Summary | 1. Finance | 2. Equity | 3. Community |

| 4. Accountability | 5. Facilities | Appendices | Members |