Online Rulemaking: Next

Steps

Robert D. Carlitz

<rdc@info-ren.org>

Rosemary W. Gunn

<rgunn@info-ren.org>

Information

Renaissance

(February 1,

2003)

DRAFT

Closely following the passage of the

E-government Act of 2002, the United States government has opened an Internet

portal (www.regulations.gov) to facilitate public participation in federal

rulemakings. This is an initial step toward creating an online environment in

which public participation in federal rulemaking may be greatly enhanced, in

terms of both the breadth and depth of the involvement. The successful

realization of this democratic ideal will depend on many details of the

implementation process for online rulemaking. This paper suggests a framework

for viewing this process and offers suggestions for the next steps in

constructing a viable system.

I. The Landscape of

Online Rulemaking

Online rulemaking will be a challenging initiative for

federal agencies to implement. The challenges arise not from any particular

technical complexity, but from the environment in which this initiative will be

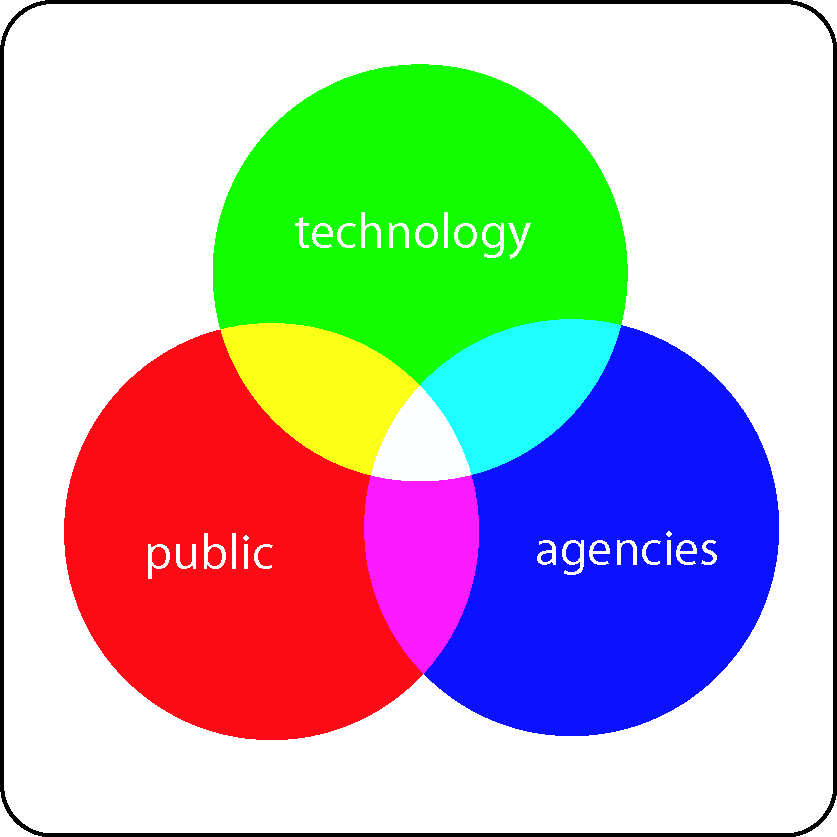

implemented. There are three major elements to consider – the agencies,

the public and the technology – as illustrated in the diagram below. First

there are agencies, many of which have rulemaking as an essential part of their

core agenda. Second, rulemaking involves public participation, and online

rulemaking will likely increase the number of attentive public stakeholders. And

third, online rulemaking requires the smooth integration of new technologies

into the practice of both agencies and stakeholder groups. These three factors

intersect in various ways, as the diagram makes clear. The intersections reflect

agency use of technology (the cyan part of the diagram), public use of

technology (yellow), public interactions with agencies (magenta), or the manner

in which technology connects the agency to public stakeholders (the white

central part of the diagram). We will discuss in turn each of the three major

factors that impact on electronic rulemaking and the many challenges inherent in

their intersections.

Factors in Online

Rulemaking

First we consider the

three individual factors.

The Agencies.

Although a handful of agencies bear the major burden of federal rulemaking,

dozens of agencies have such responsibilities. Hence a government-wide

effort to incorporate electronic rulemaking into

the practice of all agencies that make

rules will

impact many federal players. Within the federal community, there are agencies

with very different missions, histories and cultures. Each agency has its own

set of traditional stakeholders, with whom a symbiotic relationship has

typically developed over decades of interaction. In addition, each agency has a

group of internal participants in rulemaking, including program and legal staff,

public relations personnel, regulation writers, and – for online

rulemaking – IT personnel. New structures for rulemaking should not build

in processes that simply reflect “the way we’ve always done

it” but should maintain practices and information linkages that have

proven to be functional and successful. Further, if a new system is to be an

asset to both agency users and stakeholders – rather than something they

must work around – it should be designed with their participation in the

process.

The challenge of adapting a new system

to agency practice may be as great within some agencies as across different

agencies. At the same time it is clear that rethinking internal procedures can

present opportunities for reform. One example is the potential to decrease

excessive compartmentalization within agencies and the resultant barriers to

information sharing. Electronic rulemaking, by its nature, minimizes

bureaucratic compartmentalization, and the processes by which electronic

rulemaking is developed should be such as to encourage the removal of purely

bureaucratic barriers to information access.

The Public. There are currently two

primary categories of participants in rulemaking. First there are the

traditional stakeholder groups – regulated industries and their trade

associations, and public interest groups organized around issues related to

agency concerns. These organizations are typically conversant with the

rulemaking process and the technical issues that underlie a given rule. Where

they are unfamiliar with procedural or technical issues, regulated industries

will usually possess the resources needed to acquire this expertise, and public

interest groups will also often be able to do so. At least for groups that can

afford a Washington presence and their own legal and technical staff, there may

be a semblance of a level playing

field.

Individual contributors who are

relatively new to the rulemaking process make up the second group of

participants who have been active in some rulemakings. They can be expected to

increase as the process goes online. These individuals will often have had many

years of direct experience in the fields of endeavor affected by the proposed

rule; others may have experienced some personal impact. These individuals can

bring powerful anecdotal testimony to bear on the proposed rule.

We expect the interactive mechanisms of online

rulemaking to help produce ad hoc coalitions of stakeholders – or

communities of interest – as online participants become aware of one

another in their responses to a particular Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

(“NPRM”), or in discussions of a set of related issues over time.

Such coalitions might involve combinations of individual contributors and

existing public interest groups, or they may arise spontaneously as individual

contributors pool their experience and knowledge and synthesize new positions.

We regard this dynamic as one of the most exciting possible consequences of this

new approach to rulemaking.

New participants,

whether individuals or coalitions, may lack a detailed understanding of the

process itself or technical knowledge of the issues under discussion. To work

productively within the rulemaking framework, they will need more preparatory

information than the traditional stakeholders. This will increase the value of

public testimony by increasing its relevance to the rule under discussion, as

well as the accuracy of the generalizations that individuals draw from their

personal experience.

The Technology.

Several levels of technology will be deployed as part of electronic rulemaking

systems. Most obviously, there is the Internet itself, which is simultaneously

the vehicle for agencies to disseminate their NPRMs and supporting background

and analytic material, and the delivery mechanism for stakeholder responses.

Beyond access, which will be discussed below under “Public Use of

Technology,” the technology issues are twofold: storage of the information

necessary to an electronic docket, and the collection and extraction of that

information. There are multiple audiences for these processes, including agency

personnel, traditional stakeholders and new contributors, both individuals and

ad hoc coalitions. We will address the needs of these different groups in later

sections, in terms of the intersection of technology with the agencies and the

public.

Data storage. Data storage will

involve some type of database. Traditionally relational databases have been

used, and these may continue to be the repository of choice. However, cost,

speed and scalability should be considered in selecting technologies for this

purpose. With the development of low-cost, high-speed server platforms and the

existence of high-performance open-source software for these platforms, there

exists a truly wild range of prices for products of this

sort.

Data collection and extraction.

Data collection will likely be done through Web forms. Where forms are too

restrictive agencies are apt to invite the submission of attached electronic

files. Two caveats are appropriate here. (1) Forms have the nice feature of

inviting the inclusion of a number of indexing fields likely to be useful in

organizing and analyzing the information received. It is easy to envision the

translation of these fields into, for example, XML tags that can be manipulated

by commonly available software. If the same information is collected through

attached files or e-mail, there is a danger that useful indexing information may

not be included or, if it is included, that it may be hard to extract from the

document. Automated processes can attempt to find this information, but it will

be easier if it is collected up-front and with the concurrence of the submitter.

(2) Unless agencies specify standard file formats for their submissions,

preferably in terms of published public protocols, they will inevitably receive

materials that they can’t read. With electronic submissions, it’s

entirely possible that the agencies would not even be able to read the return

address, in which case they would have no way of notifying the submitter that

clarification is necessary. This level of uncertainty would be unacceptable in

any legal proceeding, to say nothing of the frustration it would cause for many

public users of the system.

Data extraction

will involve queries of two types. One type of query involves a simple search

– for example, to find individual records, such as the comment on a

particular rule by a particular stakeholder. Such queries can be easily handled

through online Web forms. The other type involves an analysis covering an entire

docket or a set of dockets, for example, a request to find the locations of all

facilities mentioned that use a particular environmental contaminant in their

industrial processes. In some cases the necessary analysis tools can be built

into the electronic docketing system. More typically, an individual or

organization interested in a complex query of this sort will need to extract all

of the records from a particular docket or set of dockets and perform the

analysis on their own system.

For this second

type of query it would be extremely awkward to use an online Web form. Consider,

for example, a docket with 10,000 public comments. If agencies follow the design

principle of “3 clicks and you’re out,” it will take 3 mouse

clicks to conduct the simple query described above; but to extract information

from the entire docket would require 30,000 mouse clicks! And if the agency did

not supply a complete index of the docket, it might be impossible to

obtain.

The solution to this problem is to

provide software access to agency databases. One available technology is

“Web services,” which allow software on one machine to make a

“remote procedure call” (“RPC”) to software running on

another machine. Through an RPC, a program on one computer can invoke the

functionality of another computer. In the present example analysis software on a

stakeholder’s computer could use an RPC to extract all comments pertaining

to a particular docket and transfer them to the stakeholder’s machine.

Modular design. At first glance it

might seem cumbersome to build mechanisms like this into the electronic

docketing system. But the same type of technology – and the same type of

data architecture – may also be very valuable at an earlier stage of the

design process. The relevant design principle is modularity, and the need for a

modular architecture relates to the great diversity of databases employed by

federal agencies at present. In a modular design different software components

communicate through standard protocols, and components from different vendors

become interoperable.

The components can then

be arranged in different ways for different purposes. A Web portal module can be

constructed to communicate with database modules running at various agencies. In

this manner the government can achieve its goal of providing a single point of

access for all federal rulemakings. But the same database modules can also

communicate with remote software through specified Remote Procedure Calls, and

this meets the secondary goal of access to agency databases for the purpose of

complex, remotely performed analyses. The modular design provides a solution of

problems simultaneously, since the Web portal can use the same RPCs to

communicate with agency databases as the analysis software on

stakeholders’ computers.

An alternative

approach to system design is superficially equivalent to our proposal for a

modular data architecture. This is simply to select one product that includes

both a Web front end for input and data extraction and a database to house this

data. The government might mandate that all agencies adopt this product for

their rulemaking records. There are several objections: (1) It is likely to be

more expensive than a modular approach. (2) Implementation of a single system is

likely to be more disruptive than implementation of a modular design. (3) The

modular approach respects the “write once; use many times”

philosophy that underlies much of today’s successful software development.

The single vendor approach is, by contrast, a philosophy of “buy once;

make everyone use it,” which is a difficult program to enforce, except in

the most rigid and hierarchical organizations.

II.

Interactions

The diagram in Section I illustrates the major elements in

online rulemaking – federal agencies, public stakeholders and available

technologies. As the diagram implies, there are a number of important overlaps

or interactions between these factors. We will discuss the issues that arise

from each of these interactions.

Agencies

and the Public. A major consideration for interactions between agencies and

the public is in the area of participation. As noted previously, the more

traditional participants in rulemaking tend to have been organized long before

the NPRM is issued, and typically possess resources that have permitted them to

take part effectively in rulemakings under the old paper-based system. These

groups will likely adapt to whatever agency structures are set up for

rulemaking. They often have in-house technical expertise and are conversant with

the legal boundaries of a typical

rulemaking.

Individual participants or members

of ad hoc coalitions are apt to appear before the agency with far less

preparation and with expectations shaped by commercial Web sites. They will

reasonably expect agency sites to be available 24 hours a day and 7 days a week,

to be easy to navigate and to comply with applicable guidelines for disability

access. They may not fully understand the structure of a rulemaking process, and

they cannot be expected to know the ins and outs of the technical issues that

underlie the proposed rule. Hence it is necessary for agencies to provide

materials – preferably online – that explicate rulemaking in general

and the current rule in particular. These materials must be more detailed and

must start at a less sophisticated level than the background materials in a

traditional docket, and they should cover the ground thoroughly enough that less

experienced players can come up to speed as full participants in the rulemaking

process. They should also spell out the ground rules for participation, lest

expectations exceed what is possible within the rulemaking process. People may

not understand that public comments are not a vote, for example. Another common

misperception is that an agency could take steps that are not possible under the

law that lead to the rulemaking. Public comment on the law might be appropriate,

but it should be directed to Congress, not the agency working to implement the

law.

Participation is always a two-edged sword

for agencies. Done well, it can increase citizen satisfaction, knowledge and

sense of ownership. It can also help broaden the knowledge of agencies and

increase understanding of stakeholder needs, and it can help the public

appreciate why and how certain agency decisions are made. Significantly for both

the agency and the public, an open process can let everyone understand that many

individuals are involved in the process – as opposed to “faceless

bureaucrats” or strident interest groups. Done inadequately, however,

participation can increase public frustration and hostility towards agency

decisions and decrease public trust in government. This means agencies will need

to plan how they will receive, review and respond to public input; to train

staff for greater interaction with the public; and – as outlined earlier

– to develop rule-related background materials for agency Web

sites.

Over a longer term rulemaking should

come out of the shadows and take its deserved place in civics curricula. After

all, the majority of laws passed by Congress lead to rulemakings, and it is

nearly impossible to read the front pages of a major newspaper without

encountering the phrase. But this is not a topic taught in high schools. Nor is

it prominent in business curricula or even law curricula. This should change as

public participation in rulemakings becomes a more common

event.

Agency Use of Technology. Online

rulemaking is not very different from other technology initiatives in terms of

how agencies can interact with contractors to achieve their objectives. That

said, it is worthwhile reiterating a few general principles. First, system

architecture should be approached from a modular viewpoint. Modules can be

defined as separate components insofar as they accomplish specific, limited

tasks and have clear mechanisms for accepting input and producing output.

Second, managers should take a high-level view of system components so as to

recognize where modules may be reused in different projects. Third, the

components must communicate by means of published protocols that meet

established public standards. Only in this manner is it possible for systems to

be interoperable among different vendors, to easily scale for high traffic

volume and to remain viable over several cycles of future product

development.

Specific components for online

rulemaking systems will include databases for document storage and front ends

for gathering information or extracting results. Some sort of

“middleware” will glue these pieces together, preferably in such a

way as to allow various levels of access and for a variety of databases and

front ends. The system should incorporate a security model to meet the needs of

both agency personnel and members of the

public.

As currently envisioned by the Office

of Management and Budget, the Environmental Protection Agency and the partner

agencies that have developed regulations.gov, the online rulemaking system will

also include analysis tools that facilitate regulation writers’ tasks.

Such tools can help analyze public comment and provide a joint authoring

environment for agency staff to collaborate on the final text of a rule. Ideally

the analysis tools should be coupled to structured input forms used for the

initial submission of comment. Through such forms commenters could indicate the

precise sections on which they wished to comment and could answer specific

questions that the agency might have posed in drafting the

NPRM.

A final issue in selection of technology

for agencies relates to cost. Since online rulemaking will eventually encompass

dozens of federal agencies, the incremental cost for additional users becomes a

significant issue. As more and more agencies join the activity, seeming

economies in the establishment of pilot systems may appear irrelevant. This is a

place where the higher development costs of Open Source systems may be more than

offset by the ability of such systems to grow with no additional costs. Open

Source systems also fit nicely into the paradigm of open standards and

protocols, which are essential for an activity of this

sort.

Public Use of Technology. As the

Internet becomes the principal route for public entry into rulemaking, along

with other government information and services, it is essential that Internet

access be open to all, with public sites where any member of the public can

participate fully. Fortunately, with Internet access now commonplace at schools

and libraries and with home connectivity becoming increasingly the norm, the

digital divide concerns of a few years ago are becoming less threatening to the

concept of an electronic democracy. Nonetheless the issue has not gone away. It

may be necessary, for example, to deploy Internet kiosks in Post Offices and

other government buildings, or to provide Internet access through voicemail

systems or TV set-top boxes.

Beyond simple

access, there are two modes of usage that will involve new technologies. The

first new mode of usage is relevant to organized stakeholders. As we have argued

previously, this group is likely to look for capture tools that allow them to

copy an entire docket to their own computer where they will use analysis tools

to help them process the information in the docket. This group of stakeholders

will also be interested in details of the technical models some commenters use

to undergird their testimony. The Internet makes it possible for agencies to

invite these commenters to make their models available online so that other

commenters can explore their behavior under initial conditions and input data

that may differ from that of their originators. This sort of “open

modeling” can help clarify complex testimony and work around some of the

mystery created by the proprietary code that may underlie the technical

models.

The second class of participants

consists of individuals and members of ad hoc coalitions. For such participants

a key feature of online rulemaking will be the way in which communications

technologies help form and bind communities of interest. Ad hoc coalitions can

become just such a community, with the technology facilitating linkages between

individuals with anecdotal information relevant to a rulemaking and those who

have the technical expertise to generalize from these anecdotes and help the

agencies develop policies that can address the problems that underlie these

stories.

Bringing it all Together. The

intersection of the interests of the agencies and the public with the potential

of the technology, as represented by the central portion of the diagram in

Section I, is where many of the ideas in this paper come together and where some

of the most innovative possibilities for online rulemaking exist. These

innovations can start with very simple steps, such as the active notification of

interested parties on rules in a given area. An expansion of the concept of

active notification could allow public involvement at earlier stages of the

rulemaking process, giving stakeholders a voice at the issue-scoping stage and

documenting the extent of participation by different sectors of the stakeholder

community.

Where issues have not been too

politicized, a broadened group of stakeholders who interact with the agency on a

given topic over time could, with the help of technology, form a virtual

community made up of the agency and the public, which shares information and

works collaboratively. The social dynamics of such a community could facilitate

negotiations, both by taking a greater range of stakeholders values and needs

into account early on and by increasing understanding of the information the

agency is working with. It could also help smooth the path for the construction

of future rules.

Of course an adversarial

element will remain, and may become sharper in the areas of enforcement and

monitoring, where access to an online record could facilitate the actions of

groups who may alert the agencies to possible violations of a given rule. We

expect some of the stakeholder community to develop their own tools for analysis

of the electronic record that will ultimately follow a rule from its initial

scoping through adoption, monitoring and enforcement. These tools will likely

operate in the context of private sites that mirror agency databases, perhaps

supplemented with other externally-generated resources.

III. The Path to

Success

The public launch of the regulations.gov Web site

(January 23, 2003) is being followed by intensive activity on the part of the

Office of Management and Budget, the Environmental Protection Agency and the

partner agencies that are working to develop a common approach to online

rulemaking. Over time these agencies will encounter major challenges,

particularly in terms of scaling to rulemakings with large numbers of

participants and paradigms for large-scale public involvement. In this paper we

have tried to highlight a number of issues that can be dealt with on a shorter

time scale and whose resolution should help facilitate the current development

process. In this section we summarize our recommendations for features that we

believe to be useful for the systems currently in the stages of design and

implementation.

- Active notification. Stakeholders should be able

to sign up for information on rules that affect a particular community of users,

independent of the agency that is working on these rules. The Department of

Transportation (DOT) is already doing this, using a simple listserv

mechanism.

- Tracking systems. Such systems could replicate the

very popular service of many shipping companies, which let customers see when

they may expect the delivery of a particular product and where that product

currently is in the shipping cycle. In the context of rulemaking, stakeholders

– and agency personnel, for that matter – could track the progress

of a given rule. This functionality is also available in the DOT

system.

- Indices. While search engines are an essential

component of online records systems, they are not a replacement for reliable

indices. Indices with hyperlinks to all archived elements are essential for

systems where the records are stored in a database, since otherwise there may be

no means of retrieving all of the available records. Also, indices are usually

much easier to browse than the results of a search – unless the search has

used tagged fields to generate what is in essence another index.

- Modular design and standard communication

protocols. To facilitate interoperability among the many agency databases

and to permit expansion from a simple electronic rulemaking system to a digital

library for all government records, it is essential to develop a modular system,

with standards for communication between modules and adherence to published

public protocols. The development of systems with reusable modules also makes it

possible to address difficult issues such as preservation and security on a

government-wide basis.

- Web services for database access. This type of

access will be important for larger stakeholder groups. It permits an

organization to copy, for example, all the materials for a given rule into a

local database for further analysis. If the systems for online rulemaking do not

include this capability explicitly, then users are apt to cobble together access

mechanisms that provide them with the same functionality – but at

significant cost in terms of efficiency to themselves and to the

government’s online system.

- Possibilities for custom front ends. The provision

of Web services that provide access to agency databases will open the door for

commercially-developed front ends that take information from these databases and

add value through analysis or supplemental data. Such custom front ends will

provide new commercial opportunities while giving the public a broader

understanding of docket materials.

- Reply comment periods. This innovation is part of

the rulemaking process followed by the Federal Communications Commission. The

idea is to split the comment period into two sections. The first section lets

stakeholders lay out their positions; the second invites comment from other

stakeholders on those positions. This structure simplifies the agency’s

chore in responding to stakeholder suggestions and can lead to discussions among

stakeholders, which have the potential to clarify viewpoints.

- Background materials. As the Internet enlarges the

audiences for rulemaking agencies will need to expand the background materials

that they provide to permit someone previously unfamiliar with the subject to

learn enough for them to take part as an intelligent and constructive

commenter.

- Open modeling. Beyond text and tables, dockets

often include the results of mathematical simulations – of economic

models, pollution transport, etc. Through the Internet, submitters can post

their models as interactive online elements. Even if the model is proprietary,

this can provide an opportunity for other commenters to experiment with it. It

can also allow more intelligent use of models in the drafting of a rule, since

it will now be possible to vary the inputs to such models and see how frangible

their output might be.

- Online dialogues. For rules that attract broad

public interest a more organized dialogue may be desirable. The Internet can be

used to conduct a moderated asynchronous discussion, using background materials

provided by the agency to lay the groundwork.

- Communities of interest. The group of people who

interact with a particular agency on a particular set of issues tends to involve

the same set of players over time. Through the dialogue that will occur in an

online docket – whether or not the agency chooses to facilitate that

dialogue through explicit mechanisms as suggested above – this group of

people may develop a degree of community. We believe this can deepen the

discussion of issues among its members and thus help the agency develop

reasonable and enforceable rules.

- Public input early in the process. There is

sometimes a perception that decisions have already been made by the time a NPRM

is published. If stakeholders can be involved at earlier stages of the process,

it may be possible to reduce acrimony and produce rules that embody more of the

sense of the broad stakeholder community. One example might be to invite broader

public input to FACA proceedings and to conduct some of these proceedings

online.

- Model participatory behavior in the development

process. One of the strongest messages that an organization sends out to its

stakeholder groups is given by the manner in which the organization develops new

initiatives. If a participatory model is adopted for the development process,

then there is some assurance that the organization is truly dedicated to

significant participation in its ongoing activities. This may be a challenge for

organizations facing tight project deadlines, but it could go a long way toward

assuring that the new systems will be truly participatory in nature.

- Continuous electronic record. While

regulations.gov focuses on that stage of rulemaking that begins with the NPRM

and ends with the published rule, that process cannot be considered in

isolation. The NPRM does not come out of nowhere, and a published rule is meant

to be enforced. Hence it makes sense to design the electronic records systems

for online rulemaking with an eye toward extensibility and to take care to

integrate these systems with agency processes that precede the NPRM or follow

publication of the final rule.

- Public role in enforcement and monitoring. With

the existence of a continuous electronic record it becomes easier for industry

and public interest groups to monitor the enforcement of a given rule. This fits

in with other objectives of electronic government – to facilitate the work

that a business must put into compliance with federal regulations and to help

citizens understand the tools that are available to help them deal with local

issues such as transportation needs, healthcare concerns or environment

degradation.

- Open source implementations for stakeholder groups.

We believe that governmental records systems should be made for mirroring,

in the sense that they must be open for access by any interested parties and

that this access should not be prejudiced in terms of certain classes of users

(such as those interested in only a handful of specific records). Thus it is

worthwhile to consider the likely architecture of systems used by stakeholder

organizations and how best these systems might connect with governmental

systems. For many non-profit organizations there is a clear trajectory toward

open-source, open-standards solutions. While this alone might not dictate that

the government adopt solutions of this sort, the systems selected by the

government should not interfere with the use of open-source, open-standards

systems by outside stakeholders.

- Structured input forms and analysis tools for

regulation writers. Structured comment forms will help commenters to be more

precise in their submissions and to answer questions that the agency may have

posed in its NPRM. These forms can be used to route materials to the agency

staff who are addressing particular issues within the rulemaking. More

generally, agency staff will need analysis tools to help them process material

received from the public. These tools will speed up the process of rule

development, increase the accuracy of agency staff work and lowering agency

costs.

- Standards for state and local governments and for

international issues. We have emphasized the need for standards for the

components of federal rulemaking systems in order for the systems of different

agencies to be interoperable with each other and with those of various

stakeholder groups. A larger interoperability problem arises with state and

local governments, but the adoption and publication of standards for federal

agencies may clear the way for a resolution of this larger problem. On a larger

scale there is the issue of international regulation. Many businesses are

subject to regulation by a number of national governments. The adoption of

standards for the rulemaking systems used by federal agencies in the United

States will be a step towards the development of interoperable online systems

for viewing regulations worldwide. In the long term this will allow the

development of “one-stop” services for businesses to view the global

regulatory environment.