Online Rulemaking: A Step Toward

E-Governance

Robert D. Carlitz <rdc@info-ren.org>

Rosemary

W. Gunn <rgunn@info-ren.org>

Information

Renaissance

1612 U Street NW, Suite 408

Washington, DC 20009

202-265-2150 (voice)

202-299-0128

(FAX)

(June 15, 2002)

(Revised July 19,

2002)

Abstract

The adoption of electronic rulemaking by many federal agencies provides

an opportunity for a greatly enhanced public role—both in terms of the

numbers of people who might participate and the depth of their possible

participation. This step towards E-governance poses several challenges for

agencies: how they should structure their proceedings, how they can process the

comments received and how they can foster and take part in the online

communities of interest that will result from this activity. The online tools

that may be applied to rulemaking and its ancillary activities—advisory

committees, advanced notices of proposed rulemaking and enforcement—can

also be used at earlier stages of the legislative process to increase public

interest, involvement and commitment. This approach is relevant for all levels

of government and for any issue on which public hearings are held or public

comment solicited. It can provide an efficient and effective non-adversarial

process in which officials and members of the public can mutually define

problems and explore alternative solutions.

I. Background

Federal agencies are moving rapidly to develop electronic systems that provide information, services and tools for the public, businesses and various levels of government. While these aspects of E-government are important, another change could have a more profound impact on the functioning of our democratic society. This is the use of computer networks to permit expanded public involvement in policy deliberations, an area sometimes described as “E-governance” to distinguish it from service initiatives.[1]

This paper will focus on a particular process that many agencies are currently converting to an electronic form—rulemaking by federal agencies—and will present a model for online participation. Rulemaking has broad impacts, since it underlies the implementation of most federal policies.[2] Since rulemaking is a well-defined and circumscribed process, and since it provides a very specific role for public input, it is an excellent area in which to explore how network access can facilitate public participation. Experimentation with rulemaking can then provide standards that can be applied more broadly.

When Congress passes a law, implementation typically involves the issuance of new rules by one or more federal agencies. Rulemaking is a common process that shows up almost daily in newspaper accounts of important federal initiatives, but at the same time is such an obscure facet of the federal government that few people not professionally involved either take part or even understand that they might be able to participate.[3] Indeed, it is unlikely that most members of the public even know this opportunity exists.

Nevertheless, federal rulemaking—as framed by the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946[4] and elaborated by legislation, court decisions and executive orders[5]—invites broad public input to every rulemaking proceeding. The basic structure is a notice-and-comment process, as sketched in Table I. An agency issues a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and announces a period for public comment. In drafting the final rule the agency must consider all material comment that has been received. Comments are not votes on the rule; rather this is an opportunity for stakeholders and interested members of the public to offer substantive analysis and criticism of the proposed implementation of the law.

Table I. Basic steps in notice and comment rulemaking.[*]

|

1

|

Notice of proposed rulemaking

|

Published in the Federal Register, with description of the proposed rule,

including reference to the legal authority under which the rule is proposed, and

a statement of the time, place and nature of the proceedings.

|

|

2

|

Comment period

|

Interested persons are given at least 30 days (and often 60 days) to

comment on the proposed rule.

|

|

3

|

Agency response

|

The agency analyzes the submissions and prepares a final rule; all material

comment must be addressed.

|

|

4

|

Preamble to final rule

|

A concise general statement of the basis and purpose must accompany the

final rule.

|

|

5

|

Publication

|

Publication of the final rule must typically take place not less than 30

days before its effective date.

|

[*] For a detailed list of steps in rulemaking under various mandates, see Seidenfeld, M. A Table of Requirements for Federal Administrative Rulemaking. Online. Available: http://www.law.fsu.edu/journals/lawreview/downloads/272/Seidtab.pdf.

Few other venues offer such a direct, compelling and effective means for public input to the process by which federal policies are developed. Yet aside from the occasional effort of interest groups to lobby for a particular outcome on a particular rule, this has not been a mechanism that most members of the public use in the course of their civic lives.

Thus while rulemaking may be the engine of the modern democratic state,[6] it remains buried in obscurity. This may be simply because it is generally carried out by public officials who are not elected; the agencies involved are not necessarily vying to be in the public eye. And though agencies now have some explanatory material on their Web sites, participation in rulemaking has not, like voting, been embedded in the public mind through civics courses and publicity campaigns as a way to have an impact on government.

Further, the type of broad public participation enabled by the Administrative Procedure Act was impractical before the widespread availability of the Internet. In particular, with paper-based systems the physical location of each agency's rulemaking docket tended to limit participation. Anyone wishing to follow the detailed course of submissions had to be in Washington, or to have a representative who could consult the docket on a daily basis.

This has limited direct citizen input, and agencies have received most of

their information in a form filtered by various interest groups.

Internet-accessible dockets change the situation dramatically. As agencies move

their dockets to electronic form, the possibility for direct public

participation becomes very real and practical.

[7]

We will argue in this paper that

E-governance can have a profound effect on the evolution of our democracy. We

look at online rulemaking as an example, beginning with the electronic dockets

that will make this possible. However, to make the most of the opportunities

offered by the Internet, it will be necessary to facilitate and broaden public

input. One model is outlined in Section III, followed by a discussion of

additional benefits and broader applications to be gained from online

activities.

A concerted effort is now underway to develop electronic dockets[8] [9] for federal agency rulemaking. With leadership from the President’s Management Council (PMC) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the Department of Transportation (DOT) is currently managing an effort to implement a government-wide Online Rulemaking Initiative.[10] This effort will provide a common approach for the construction of electronic dockets by federal agencies with major rulemaking activities, building on previous work of DOT and others.

From the perspective of the PMC, online rulemaking is one of 24 initiatives in electronic government[11]. Although electronic rulemaking is classified by OMB as a government-to-business initiative,[12] rulemaking can, with enhancements such as those described in Section III, also be an important part of E-government for the public.[13]

From the agency standpoint, an efficient electronic process for the management of information will cost less than the operation of a paper system, may help to avoid litigation, and will ease the tracking of a proposed rule as it evolves through the system. Precisely these efficiency considerations drove the adoption of an electronic docket at DOT. This system was designed to replace the agency’s old paper system. New materials for any rulemaking are quickly entered into the system, and the electronic records become and remain the primary record for the agency. This avoids duplication of records and does away with the need to retain and further organize paper input. As a result, the agency has reported cost savings of more than a million dollars a year, largely through the elimination of clerical staff and redundant storage facilities.

In moving to electronic dockets, several policy and implementation areas deserve careful attention:

Transparency. Electronic dockets have the potential for improving the sharing of agency information, both internally and externally. While traditions of practice may have limited sharing, recent reforms[14] go in the direction of greater transparency, creating structures that allow agencies, stakeholder groups and other members of the public to track the progress of issues through the agency.

Several factors support the idea of transparency as more than an E-government buzzword or a “good government” goal. Regulated entities find it easier to do business when the process of regulation is more predictable. Agencies themselves have a need to organize and access information across internal agency boundaries. When information is not readily available, an agency is apt to be less efficient in assessing and reacting to its environment, including its ability to defend or enforce existing regulations, or to incorporate stakeholder viewpoints in new rules. We regard such reforms as essential to the success of public participation, and—equally importantly—to the agencies’ ability to deal effectively with information.

Going beyond paper. Electronic dockets allow for a level of accessibility and interactivity that was impossible with paper dockets. Hence, as agencies construct electronic dockets, they should avoid constructing mere replicas of their paper dockets, which might enshrine limitations of the paper dockets in the new electronic systems. These limitations go beyond the obvious fact that paper dockets are expensive to duplicate and distribute and that they take up a lot of space.

DOT’s electronic system allows rapid access to the docket by agency staff, as well as external stakeholders. But the system is not perfect. For example, in its present form paper input is scanned but not converted to electronic text, so the system’s search capabilities are very limited. Deficiencies will be overcome as DOT revises its site and extends its text conversion and search capabilities as part of the current OMB initiative. The agency will also be able to take advantage of experience gained in several parallel efforts within the federal government. The new electronic docket system at the Environmental Protection Agency, for example, provides a well-designed initial user interface.[15] Other examples available to the DOT-led task force should allow the specification of a high-quality common approach.

Common standards, common access. It will be preferable to achieve the commonality sought by the PMC in terms of standards for data description and presentation, rather than a merger of existing systems or a single prescribed new system. Common standards allow interoperability of systems provided by different agencies and enable a common user interface, but they do not require absolute uniformity. While uniformity might seem desirable, it ignores the very different requirements and cultures in the various agencies, which reflect their different histories and constituencies.

There is of course a need for uniformity from the perspective of the regulated industry and the public at large—the external users of an electronic docketing system. A new business seeking to comply with federal regulations should not have to search out the individual agencies that have authority over it. Rather it needs a way of finding these agencies—and their rules—through some common gateway. Similarly, members of the public concerned about local environmental or development issues should not have to search for the agencies involved; they should be able to find these agencies by following their issues of interest.

OMB has recognized these needs in its current work to develop electronic dockets as extensions of FirstGov.[16] Within the limitations of their approach—which focuses mostly on the internal needs of the agencies and the concerns of the businesses that they regulate—we expect their work to advance the idea of electronic rulemaking in a significant and expeditious manner.

Cross-departmental planning. We believe that for best results, an agency’s program staff, rule writers, legal and information technology staff, and others must work together to assess needs and specify how to adapt existing procedures to conform with the new standards. Within DOT, an internal working group headed by personnel in DOT’s Office of General Counsel drew up specifications for such a system in 1994. Significantly, in addition to Office of General Counsel staff, this working group included others—technical staff and rule-writers from agencies within DOT. The group’s recommendations received the endorsement of the Department Secretary and launched a project that led to DOT’s present electronic docketing system.

Organization, searchability and analysis. These are problematic issues with paper dockets, which can be addressed when dockets move online. Agencies do not typically impose any structure on paper submissions. Some agencies may suggest length limitations, but these are easily circumvented by attachments, which are not subject to these limits. While some attachments may be relevant and germane, submitters may puff up their submissions with photocopies of marginally relevant materials, often reproduced in semi-legible formats.

With no guidelines for submission, it is no surprise that agency staff often

have a hard time in processing the comments they receive. Since the agency is

under a statutory requirement to respond to all material input, it can be a

severe burden for agency staff to sort through just what is being said. When

large-scale proceedings are under way, an agency may contract for a

“content analysis” of submitted comments. In essence this approach

provides a detailed catalog of the submitted material. Some vendors offer

automated procedures for doing this type of cataloging, but we doubt that a

purely mechanical procedure will be adequate for this task.

Information

Renaissance has suggested that the best cataloging of submitted material would

be done by the submitters

themselves.[17] This would need to

be carefully designed. One initial step would be for agencies to experiment with

structured comment submission

forms,[18] which submitters can use

to organize their comments, section by section, on the proposed rule.

Experimentation is needed here, since an agency must strike a balance between

structures that facilitate the sorting and processing of submitted comments and

structures that hinder the expression of clear and concise thought.

While the focus in the government-to-citizen sector of E-government has been in the area of services, polls have suggested widespread public interest in the potential of the Internet as a means to empower citizens and increase the accountability of government.[19] Federal rulemaking has some features that make it a particularly appropriate starting point: (1) similar principles govern the procedures of most federal agencies; (2) the subject of a given proposal is very clearly delineated; (3) a sizeable (though not necessarily representative) set of stakeholder groups already participate; (4) the period for comments is circumscribed; and (5) agencies normally issue a rule following the receipt of public comments.

Online rulemaking can be a significant step towards real public involvement, going far beyond questions of efficiency and economy to address public interest in governmental decision making processes, trust in government, and commitment to governmental decisions. We believe that meaningful, non-adversarial interactions between the public and public officials can expose participants to a broad range of viewpoints and result in better understanding, better policy decisions, and more effective implementation. We hope this will ultimately create a space for the mutual definition of problems and exploration of alternative solutions.

In this section we will talk about mechanisms for public involvement in online rulemaking. In the next we will consider how E-governance might change the dynamic of groups of people—inside and outside an agency—who interact on a regular basis to address issues of common concern.

The simplest consequence of having an agency’s docket online is that people can follow and contribute to an agency proceeding from their offices or homes. This can substantially increase the circle of people involved in a rulemaking. We aren’t thinking solely in terms of numbers here, since rulemaking is not a vote. Rather there is the potential to have more points of view entered into the discussion, to explore the full range of possible solutions to the problems addressed by the proposed rule, and to be able to anticipate difficulties with the enforcement of any proposed solution. In this sense greater public participation can lead to better rules—rules less likely to be challenged in court, rules more capable of uniform enforcement and rules more likely to be followed by the regulated entities.

The step of placing a docket online and allowing the electronic submission of comments is simple and relatively inexpensive to implement, and has the potential to expand the audience that participates in a rulemaking process beyond interest groups and professional experts to include other stakeholders and members of the general public. Each of these individuals and organizations has something to offer, but for any given rule it is not a priori obvious who will provide the most significant contributions. The present system is biased heavily toward interest groups and professional experts. This may have its advantages in terms of keeping the quality of input high, but it can fail in areas where rapid technical progress may have left interest groups behind or rendered traditional experts somewhat irrelevant, or where public values are important to successful implementation. A process that is open and welcoming to all comers avoids such pitfalls. It will also help agencies broaden their base of constituent understanding and support.

However, making dockets available and allowing online submissions alone will not guarantee the input of well-informed, incisive and useful comments. The agency must educate a broader public about what is involved. This requires explaining the rulemaking process, the bounds of acceptable comment, and what is involved in submitting a comment. It also requires a presentation of background information on the particular rule under discussion, and outreach to a broad group of potential stakeholders.[20] The presentation of a rule in context will become easier if units of the government develop a continuous electronic record of their activities. These amendments will not provide a level playing field for all participants, but are a step in the right direction.

With an open process—and a rapid turn-around between the submission of comment and its availability for public scrutiny—the dynamic of the traditional notice and comment process is likely to change. Once it is easily possible to reply to others’ comments, the process may evolve in the direction of a discussion or dialogue.

We believe that this will be a very useful innovation and one worthy of formal encouragement. Indeed we would advocate a process much like that presently carried out by the Federal Communications Commission, where the comment period takes place in two stages. The first stage allows for an initial statement of positions, while the second stage invites replies to comments made in the initial round. This approach is less vulnerable to “gaming,” when, for example, submitters wait until the last possible minute to enter their comments in the hope that their statements will go unchallenged by other commenters.

Beyond the two-step comment process, we propose that rulemakings of great public interest should be accompanied by an interactive, moderated, asynchronous online dialogue, in which stakeholder groups and individuals are able to learn more about the proposed rule, express their opinions, hear other viewpoints and offer suggestions for changes.

Logically, an online dialogue would be an integral part of the notice and comment process. It could also coexist with that process, in which case the online discussion would be separated from the rulemaking, but participants would have the option of submitting comments to the rulemaking as desired.

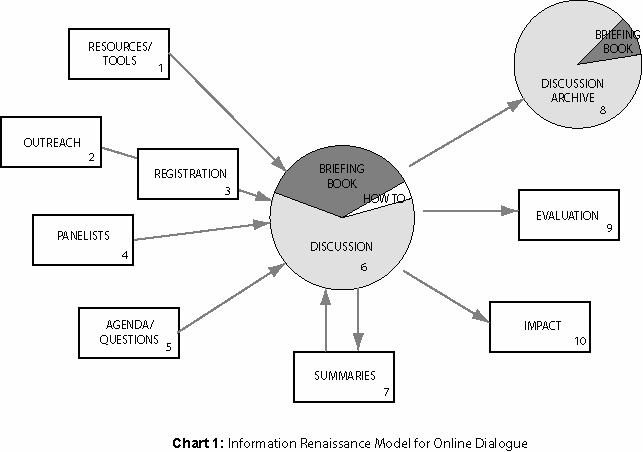

In recent years, Information Renaissance[21] has developed a model for online dialogue that could work well as an adjunct to rulemaking. Briefly stated, the model is as follows. (See Chart 1 for a graphic representation.)

Our first experience with this type of event was in the context of the “E-Rate” proceeding at the FCC, [23] which took place following the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and has since helped schools and libraries to connect to the Internet. Information Renaissance noted that of the several hundred comments received by the FCC in its standard paper proceeding, only two came from school districts—even though there are approximately 16,000 school districts in the country and these school districts stood to benefit to the tune of more than a billion dollars a year if the proposed E-Rate rule was implemented.

School districts were represented in the FCC’s proceeding by Washington-based trade associations, but had little advance knowledge of the mechanisms that were being proposed for implementation of the E-Rate. These would require extensive paperwork on the part of the school districts and libraries and a good deal of preliminary work in terms of technology planning. The online dialogue served the dual purpose of soliciting input from school districts and libraries around the country, and helping to educate them about the steps they would need to take to participate in the E-Rate program.

As with any other rulemaking, there were several elements that participants needed to understand if they were to take part. Obviously these included the nature of the rulemaking process itself. Also, they needed to understand the technologies that were to be subsidized under the proposed program. Finally, they had to appreciate the needs of the education and library communities and the ways in which technology might address these needs. Three groups possessed knowledge of these individual elements: staff at the FCC were well-versed in the rulemaking process; people at the telecommunications companies knew the technologies that were available; and teachers and librarians understood the application needs. The online dialogue brought these groups together.

Since this 1996 event Information Renaissance has conducted a number of additional dialogues on public policy issues and has refined its model, as described by the ten points listed above. The E-Rate dialogue did not include panel discussions, but it had many of the other elements, and it incidentally included the first electronic rulemaking docket, which Information Renaissance compiled by scanning a paper docket purchased from the FCC’s copy contractor.

In evaluating these events, which have been highly valued by participants and noteworthy for the non-adversarial character of the discourse[24] (in comparison, for example, to some public hearings), we have come to believe that the structure around which a dialogue is built is critical to its success. The Information Renaissance dialogues have been based on exhaustive reference material, seeded with diverse panels of experts and attended by staff who review incoming messages and may assist participants behind the scenes. This structure and the manner in which the event is presented help to set the tone. However, several issues will require resolution as online dialogues are deployed more generally:

First Amendment Issues. Since online discussions are a relatively new mechanism for gathering public input on federal policy issues, there is some uncertainty as to the nature of the activity and the rules that should be applied. Is it an open forum in which participants should be able to speak on any topic in any tone they choose? Or should there be guidelines for participants? In an online dialogue developed for the EPA we were advised by EPA’s Office of General Counsel not to exercise any of our usual prerogatives as moderators. They felt that First Amendment concerns prevented the application of discretionary decisions on the posting of individual messages. Other agencies have taken a different approach. It remains for the Department of Justice to provide clarification of the legal nature of an online dialogue and the appropriate bounds for the moderators of such a discussion. This includes questions of people speaking on-topic, of the number and length of postings and of the language used.

Privacy. The Privacy Act of 1974[25] provides a code of information practices that attempts to regulate the collection, maintenance, use, and dissemination of personal information by federal agencies. EPA’s Office of General Counsel has interpreted this Act narrowly to discourage the maintenance of author indices for messages in the archive for an online dialogue. EPA’s outlook differs from that of some other agencies, and a uniform decision would be useful.

Copyright Protection. The use of an electronic docket facilitates a broader dissemination of materials submitted as comment or in support of comment in a rulemaking proceeding than with a paper docket. This leads to a number of copyright issues, which also call for uniform interpretation and enforcement.

Public Access. At present, those who do not have access to a computer

at home or work can take part in online exchanges by using a public access

computer. Although access is increasing, it is far from ideal. Many libraries

have computers available, but time may be limited. More public access points are

needed; in the long term we expect to see ubiquitous Internet access, whether

via the convergence of video, data and voice over a single common link or

through the extension of Internet services to a number of commonly-used

electronic devices.

Standards. If online dialogue is to increase

public interest in government and commitment to the outcome of rulemaking and

other official procedures, several conditions must be met, including inclusive

outreach; non-partisanship; balanced information, selection of panelists, agenda

and questions; and fairness in treatment of participants. A common set of

guidelines would be very useful.

IV. E-governance in

Practice

We have argued for rulemaking procedures that go beyond putting paper processes online, and make use of technologies that move towards E-governance. We believe the possibility of seeing others’ comments as soon as they are submitted and the availability of mechanisms for replying to these comments will encourage stakeholder dialogue. Further, we have advocated that a structured dialogue—in the form of an asynchronous and moderated online discussion—be incorporated into all rulemakings that warrant it. A simple mechanism might be to develop background educational materials for every rulemaking, to provide an online signup for people interested in a dialogue and to trigger such an event whenever the number of interested people exceeds some predetermined threshold—a few hundred people, for example.

In this section we speculate on the consequences of such a policy, including the likely process impacts of this aspect of E-governance on agency operations. What happens during a dialogue, apart from the stated discussion? First, an online dialogue is very different from a static set of comments submitted to an agency, whether on paper or in electronic form. Dialogue implies a conversation among participants, not just a series of statements directed from participants to the sponsoring agency. While agency personnel may participate by adding information to the dialogue—e.g., to clarify points of fact about agency policy—the agency will also have the opportunity to hear the pros and cons of various stakeholder positions. As alternate positions are presented, there will be opportunities for discussion and criticism of these alternatives. This will help the agency to respond to suggestions, and it will reveal areas of agreement among contending stakeholders.

Second, a dialogue inevitably involves individuals, not just interest groups and their representatives. This has several implications. For one thing, it changes the role of interest groups in a subtle manner. While interest groups are free to recruit participants to take part in a dialogue, individual participants may diverge from the institutional position on some issues. Also, the individuals who participate in a dialogue undergo a degree of socialization. This, plus the slower pace of a dialogue relative to a public hearing, smoothes the edges of contentious issues and enables a more tolerant and civil exploration of topics for which there is no consensus. For agency staff there is a dual benefit: strong emotions are diluted and emotional positions may be discussed among and come to be better understood by stakeholders, rather than directed solely at the staff.

Of course the socialization within a dialogue extends to the agency staff themselves. Particularly in the current phase, when online dialogue with government agencies is something of a novelty, members of the public are likely to react very positively to staff members who put personal time and effort into such an activity. And participating staffers generally respond positively to “real people” bringing their personal experiences and viewpoints to the discussion.

Participation in an online policy dialogue can be demanding. Indeed, we would advocate that agencies set the bar quite high, not compromising the level of public discussion simply to attract a larger audience, but making sure that no groups are excluded because the necessary information is not available to them. To this end we believe that agencies must find ways to explicate their proceedings to the general public in enough detail so as to enable intelligent participation. Information should be tailored to the needs of stakeholder groups. For example, in a discussion of a rule related to welfare policy or other issues that affect low-income people, special attention should be paid to developing materials useful to a variety of reading levels and to outreach, both for purposes of notification and to encourage the use of public access computers to take part.

This would be a significant change from current practice, where professional experts tend to dominate the proceedings. Without downplaying the knowledge of experts, we think that in a democracy, issues of public policy should be understandable by the public at large. We will discuss these issues further in a forthcoming evaluation of the recent online dialogue organized by Information Renaissance and involving the public, with members of the California legislature, in discussions of California’s draft Master Plan for Education.[26]

Regular online exchanges are apt to have an additional effect. Just as at present, the same groups are likely to appear before a given agency on a series of related topics. Experience with electronic mailing lists and other online groups suggests that the communities of interest that emerge may stay in touch, reinforcing the socialization discussed above.[27] Online exchanges, combined with an increased transparency, could make these communities broader, more cohesive and more collaborative than at present.

Online interactions may also help the divisions of an agency to discover

common interests and new incentives for internal information sharing. As agency

processes become more transparent to outside observers, they will also be more

transparent across divisions: if members of the public can trace the

information flow within the agency, then agency staff can do the same thing.

Opening up the flow of information may lead to a fundamental reordering of

agency procedures. The “silos” or “stovepipes” that are

said to separate the divisions of government agencies must diminish in

significance. And the agencies’ reward systems will need to adjust to a

new environment.

These are big issues—no bigger, perhaps, than the idea

of opening federal procedures to the direct participation of millions of

citizens, but still daunting in the face of many decades of institutional

inertia. We regard public participation as a positive and potent force in a

democratic society, and see this as the essence of E-governance. Our hope is

that institutional streamlining and reform will be another positive result.

The ideas we have presented for enhancing public involvement in rulemaking can be more broadly applied to help make E-governance a reality. In addition to the rulemaking process itself, state and federal agencies engage in many ancillary activities—either preceding the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking or following the promulgation of a final rule. These include issue scoping within agencies, advisory committees, advance notices of proposed rulemaking, and enforcement procedures. Outside the rulemaking arena, a multitude of policy-making processes invite public input, typically through notices requesting public comment or public hearings. In most of these processes, the sponsoring units of government could profitably extend public input to online form.

Apart from rulemaking, Information Renaissance has produced several online dialogues on policy issues. In 1999 we worked with Americans Discuss Social Security to produce a dialogue on Social Security reform—with the participation of thirteen members of Congress and thirteen other experts as members of online panel discussions.[28] In 2001 we worked with the EPA to produce a dialogue on the EPA’s draft public involvement policy.[29] And, as noted, in 2002 we worked with a joint committee of the California legislature to increase public input on the state’s Draft Master Plan for Education.[30]

The most successful of the online events—in terms of satisfaction on the part of the public participants and the agencies with which we have worked—have been those that most closely match the five features listed in the first paragraph of Section III. In particular, people appreciate an event that starts with something tangible—such as a draft document or a scenario for issue framing—and leads to something specific—such as implementation of the policy described by the document or the selection of specific issues for further action.

But many public processes meet these criteria. On the local level there are, for example, various development projects and highway construction projects. At the state level there are discussions of education policy or telecommunications policy or transportation policy. All of these issues lead to the expenditure of significant levels of public funds, and many attract the interest and concern of some significant fraction of the public.

Many of the points made earlier apply to these online processes, including a need for transparency, a need for a carefully planned structure, and a need for high standards of non-partisanship and balance. In addition, to sum up:

Outreach and education always deserve attention. Mailing lists should be established to provide active notification for interested stakeholders. People could sign up for these lists, indicating areas of interest, and be notified of all activities flagged by the keywords they select. Background material should be routinely supplied to explain the legal processes involved and the specific contents of the rules or policies under discussion. Materials should be presented at different levels of sophistication. An introductory presentation would enable people unfamiliar with the topic to participate; more advanced presentations would provide access to relevant information in detail.

A continuous electronic record should be developed where feasible. This would make governmental procedures more open to the public, clarifying both the origins of an action and the process by which it was developed. Such a record would provide stakeholders and interested members of the public with a clear picture of how a given rule evolved and how effectively it is enforced.

Interactive mechanisms may be as simple as accepting e-mail or Web submissions of comment, although as with rulemaking the level of public input would be significantly enhanced if educational materials tailored to the stakeholders were provided online. For issues likely to attract a wide audience or likely to provoke contentious discussion, more interactive methods like online dialogues would be useful to encourage give and take. In some cases it may be possible to begin to explore what Coleman and Gøtze call “active participation” in which—while decision making authority remains with government—citizens have a role in “proposing policy options and shaping the policy dialogue.”[31] All of these interactive activities should involve public officials and staff in more than a passive role—answering questions, moderating discussions and facilitating stakeholder involvement.

As Internet use becomes ever more embedded in American society, mechanisms such as these can be used to bring together officials and members of the public to mutually define and discuss problems and explore alternative solutions, serving as a force to increase mutual involvement and commitment. Further, a better-informed citizenry that pays attention to government will be far better equipped to hold leaders accountable. What remains to be seen is how quickly the United States will, as other nations,[32] begin to work towards making public involvement a significant part of E-government.

References

[1] Simpler steps towards

E-governance or “E-democracy” include the active use of comment

forms, online surveys and focus groups to increase government responsiveness;

online committees, public hearings and testimony, and video conferencing. See

for example Steven Clift, Top Ten E-Democracy “To Do List” for

Governments Around the World. Online. Available:

http://www.publicus.net/articles/egovten.html.

[2]

“Under the APA [Administrative Procedure Act], any agency decision that

sets binding obligations or standards for a class of people is a

‘rule.’ Rules made by regulatory agencies have the force and effect

of legislation.”

North American Commission for Environmental

Cooperation. N.D. Online. Available:

http://www.cec.org/pubs_info_resources/law_treat_agree/summary_enviro_law/publication/

us06.cfm?varlan=English.

[3] Kerwin, C. (1998, 2nd ed.).

Rulemaking: How Government Agencies Write Law and Make Policy. CQ Press,

Washington, DC.

[4] Administrative

Procedure Act, US Code Title 5, Section 553 (Rulemaking). Online. Available:

http://www.oalj.dol.gov/public/apa/refrnc/553.htm. OMB Watch gives a summary at

http://www.ombwatch.org/article/articleview/176/1/67/.

[5]

Legislation includes: the Paperwork Reduction Act, the Small Business Regulatory

Enforcement Fairness Act and the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act; court decisions:

Weyerhauser v. Costle, 590 F.2d 1011, 1030-31 (1978, DC Circuit). Portland

Cement v. Ruckelshaus, 486 F.2d 375, 3939-94 (1973, DC Circuit), cert. denied

417 US 921 (1974); executive orders: 12,291 and

12,886.

[6] Kerwin, op.

cit.

[7] A detailed legal

discussion will be found in Brandon, B.H. & Carlitz, R.D. (2002). Online

Rulemaking and other Tools for Strengthening Our Civic Infrastructure.

Administrative Law Review,

forthcoming.

[8] “Dockets are

formal inventories of materials making up the record in a proceeding.... as a

practical matter the docket defines the record.” Perritt, H.H. Jr.

Electronic Dockets: Use of Information Technology in Rulemaking and

Adjudication. Online. Report to the Administrative Conference of the United

States. Available:

http://vls.law.vill.edu/academics/jd/courses/

administrative_law/faa.htm#rfn59.

[9]

Another aspect of E-government is evolving legislatively, with Senate Bill 803

(Senators Lieberman and Thompson). This bill establishes a broad set of new

initiatives, which will require the federal government to use Internet-based

technology to enhance citizen access to government information and services and

fund a set of projects to help agencies deploy these technologies. S.803 was

unanimously adopted by the Senate in June, 2002, but its future progress and

funding are not yet clear. To see the legislation, enter the bill number in the

Thomas search engine at

http://thomas.loc.gov/.

[10]

Office of Management and Budget (2002, February 27). E-Government

Strategy. Online. Available:

http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/inforeg/egovstrategy.pdf.

[11]

Ibid.

[12] OMB has

classified these initiatives as government to citizen, government to business,

government to government (within the federal government or between federal and

other levels of government) and internal efficiency and effectiveness. Ibid;

also see

http://www.egov.gov/egovreport-3.cfm.

[13]

This would seem to be consistent with the goals stated by President Bush of a

government that is responsive, results-oriented and citizen-centric. See Office

of Management and Budget (2001, August). The President’s Management

Agenda, Fiscal Year 2002, p. 23 and 4. Online. Available:

http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2002/mgmt.pdf.

[14]

Graham, J.D. (2001, October 18). Office of Management and Budget, Memorandum

for OIRA Staff, Online. Available:

http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/inforeg/oira_disclosure_memo-b.html. This memo

describes the significant steps taken by OMB in placing deliberations of the

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs regarding proposed federal rules

online for public access. At the same time the administration has

been more reticent than its predecessors in other areas, withdrawing previously

published information from federal Web sites in some cases and urging agencies

to release the minimal amount of material consistent with the Electronic Freedom

of Information Act. See Ashcroft, J. (2001, October 12). Attorney General's

Memorandum On FOIA. Online. Available:

http://www.usdoj.gov/oip/foiapost/2001foiapost19.htm. Some of this caution is a

justifiable response to terrorist threats, but there remains a palpable tension

between the promise of open government offered by the existence of the Internet

and the instinct of governmental organizations to maintain tight control of the

information they possess.

[15]

http://cascade.epa.gov/RightSite/dk_public_home.htm.

[16]

FirstGov (http://www.firstgov.gov/) provides gateways to US government

information for citizens, business and

government.

[17] Brandon, B.H.

& Carlitz, R.D. (2001, February 28). Online Rulemaking: A Tool for

Strengthening Civic Infrastructure. Congressional Internet Caucus, E-Government

Briefing Book. Online. Available:

http://www.netcaucus.org/books/egov2001/9.

[18]

See, for example, the approach used by HHS for their rulemaking on medical

privacy. Online. Available:

http://erm.hhs.gov/hipaa/erm_rule.rule?user_Id=&rule_Id=228.

[19]

Hart, P. & Teeter, R. (2001, January). Public opinion survey for the Council

for Excellence in Government. Online. Available:

http://www.excelgov.org/techcon/egovpoll/reptjan/final.PDF. This topic is

covered in more detail in the August 2000 report, at:

http://www.excelgov.org/

techcon/egovpoll/datasets/final1.htm.

[20]

One example is the extensive outreach effort of the Forest Service for its

proceeding on roadless areas: Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation, 66 Fed.

Reg. 3,244 (2001) (to be codified at 36 C.F.R. pt 324). The dedicated Web site

for this rulemaking is available at

http://roadless.fs.fed.us/.

[21]

Information Renaissance (http://www.info-ren.org/) is a non-profit organization

that develops infrastructure for public access to the Internet and uses

technology to increase citizen input to government.

[22] Felleman, J. (1999).

Internet Facilitated Open Modeling: A Critical Policy Framework, Policy Studies

Review, 16 3/4 193-216. Online. Available:

http://www.esf.edu/es/felleman/OpenMod/OM-Paper.html.

[23]

Online. Available:

http://www.info-ren.org/universal-service/network-democracy/.

[24]

Beierle, T.C. (2002, January). Democracy On-line: An Evaluation of the

National Dialogue on Public Involvement in EPA Decisions. Online. Resources

for the Future. Available:

http://www.rff.org/reports/PDF_files/democracyonline.pdf.

[25]

5 US C § 552a (2000).

[26]

Gunn, R.W. & Carlitz, R.D. (2002). E-democracy: Dialogue at State

Level. To appear online.

[27]

This idea is related to the concept of “communities of practice,”

currently being explored by the Federal CIO [Chief Information Officer] Council

(http://www.fgipc.org/02_Federal_CIO_Council/communities.htm). One project that

is a beginning towards an open discussion is the Federal Highway Administration

site “re: NEPA” (National Environmental Policy Act) at

http://nepa.fhwa.dot.gov/ReNEPA/ReNEPA.nsf/home.

[28]

Online. Available:

http://www.network-democracy.org/social-security/.

[29]

Online. Available: http://www.network-democracy.org/epa-pip/. See also Beierle,

op. cit.

[30] Online.

Available:

http://www.network-democracy.org/camp/.

[31]

Coleman, S. & Gøtze. J. (2001, December). Bowling Together: Online

Public Engagement in Policy Deliberation, Chapter 2. Online.

Available:

http://bowlingtogether.net/chapter2.html.

[32]

In the US, Firstgov (http://www.firstgov.gov/) offers links to information on

services and a Federal Register page on participation in rulemaking

(http://www.firstgov.gov/), and national E-government Web sites have begun to

appear (General Services Administration, at http://egov.gov/index.cfm; see also

http://www2.ctg.albany.edu/egovfirststop/). For E-governance, while a number of

federal agencies (and one Senate Web site), state governments, non-profit

organizations and researchers have carried out experiments, national-government

sponsored strategy and implementation appear to be further advanced in other

countries. See for example the Canadian site, “Crossing boundaries”

(http://www.crossingboundaries.ca/cbv32/index.phtml?section=about_main); the

Australian site “Government online” (http://www.govonline.gov.au/);

and the United Kingdom E-democracy site “In the service of

democracy” (http://www.edemocracy.gov.uk/). Links to many international

sites are available at http://www.egovlinks.com/world_egov_links.html. For an

overview, see e.g. Riley, T.B. (2001, September) Electronic governance and

electronic democracy: Chapter three, “Developments in Canada, UK and

US—A comparison.” Online. Available:

http://www.electronicgov.net/pubs/research_papers/eged/chapter3.shtml; and

Poland, P. (2001, December) Online consultation in GOL countries: Initiatives

to foster e-democracy. Online. Available:

http://www.governments-online.org/documents/e-consultation.pdf.