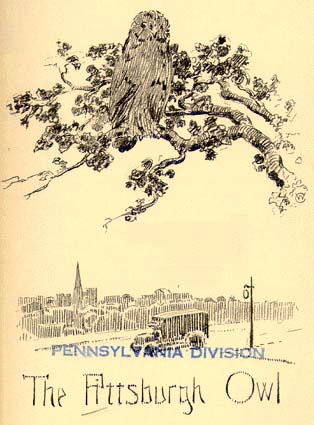

"Phineas," said I at breakfast one morning soon after we arrived in Pittsburgh, "I heard an owl last night."

Phineas arranged a drop of Pennsylvania apple-butter on a bit of toast before he replied.

"Don't you think," said Phineas, "that it was a truck?"

"Do trucks hoot for half an hour from the same tree," I queried midly, "and every now and then stop hooting to cluck?"

"The horns on trucks," observed Phineas non-committally, often sound very much like owls. You listen critically, and see."

A person who has heard sounds that another person has not lacks backing in an argument. We were only just in from our ride across the Alleghenies, where there had been plenty of owls hooting in the mountains as we coasted in the moonlight down the long road that Washington surveyed. Phineas and George Washington and I had heard them, and their tone-quality was fresh in my mind. Still, I was conscious that owls were improbable in the vicinity of the Negley Avenue Hill.

But next morning Phineas was to take a very early train, and I was getting breakfast before daybreak in the kitchenette. The Pittsburgh owl began to hoot diligently from the direction of the trees on Fifth Avenue. It was unmistakably an owl. Not a truck.

"Phineas," I called softly from the kitchen, "hear the owl."

"What?" murmured Phineas, still nearly asleep.

"Hear the owl," said I sociably. "It's time to get up."

"I can't give you any minutes," said I virtuously. "You talk as if I kept the minutes. You talk as if I were the agent--"

"Of the devil?" suggested Phineas in a muffled voice.

"No," said I, still unquenched, "of the morning. You talk as if I were the Agent of the Morning. I didn't write the time-table. Hear the owl!"

(Great demonstration by the owl off-stage at this point. Not the rapid hoo-hoo-hoo of an automobile horn, but a medley of heart-broken wails with untrucklike variations, and now and then an interval of soprano hooting interspersed with clucks.)

"Did you hear it?" I asked, taking the grapefruit to the dining-room.

"I guess so," groaned Phineas, to pacify me.

"Well," said I brightly, "wasn't it a Treat?"

Later, at breakfast, I made the mistake of recapitulating.

"You did hear the owl," said I, "didn't you? It was just the same as what I heard last night."

"Well," said Phineas judicially, "you know it probably was a truck."

When one has always thought of a famous city as being made up largely of smoke and cinders and the Labor Question, any little variation from the advertised normal comes as a surprise. I was perfectly delighted to find one of the most civilized and fully settled areas blossoming forth with owls.

Newcomers in Pittsburgh often spoil their own first impression in this way--looking longingly for something that belongs properly somewhere else, and telling the old residents how unfavorably Pittsburgh compares with Santa Barbara, or Washington, or Boston-by-the-sea, or other cleanly spots. Pittsburgh takes this calmly and expects to be disliked. If you admit a sort of sneaking fondness for the busy, rumbling town, the wary old-timers cast a penetrating eye upon you, and suspect you of playing Glad Games, or of speaking patronizing words of cheer. This is one of the charms of the place. It has no local conceited cult, and it pretends to be nothing that it is not.

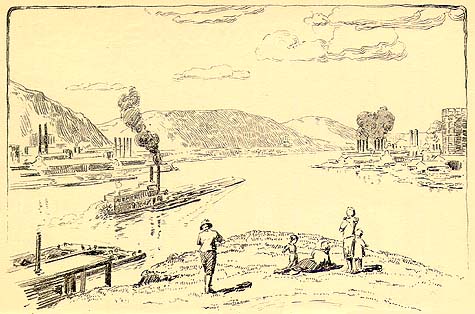

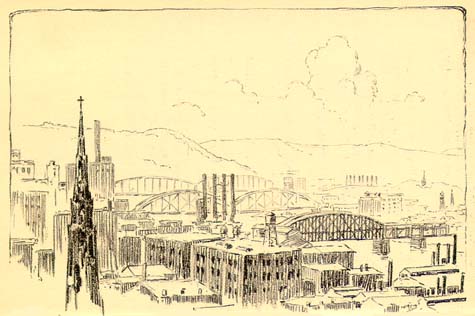

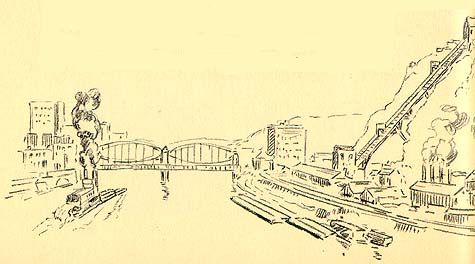

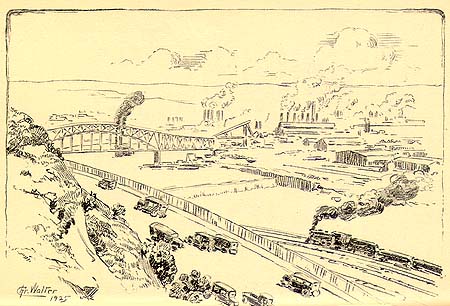

There it sits, on its strategic "Point," its three rivers bristling with industry, its bridges black with traffic, its boulevards all exceeding the speed-limit, its city fathers striving every year to keep the rate down to thirty miles an hour. When we were new in Pittsburgh, the traffic officers kept telling us to "drive faster." In Boston, we had been considered quite a reckless pair, to be narrowly watched for spurts of speed and daring. But in Pittsburgh, we found with some little indignation that we were what is locally called "road-mopes." We noticed that our Pittsburgh policemen were fully equipped for business with cartridge belts around their ample waists, and so we sped along at a great rate as they told us to. We were afraid that if we did not go fast enough to suit them we might get a bullet in our rear tire. When we reported our experiences with the traffic officers to friends, they said, "Oh, yes, they have to get the traffic out of the way." That is just it. Time was when we thought of policemen as persons appointed to stop traffic. In Pittsburgh they shoo it along.

One day a huge moving-van collided with a limousine, and an undertaker's wagon arrived ahead of the ambulance or the police. They believe in getting the most needed appliances to the spot first. The true Pittsburgh motorist also believes in driving on the wrong side of the road whenever the fancy seizes him; and he considers it pedantic to park on the right side of the street. When I noticed this, I gave up learning to drive. The distinction between right and left was hazy enough in my mind as it was.

But the most interesting phase of independence that we observed was the efficacy with which a flock of automobiles can enforce their wishes when for any reason they are held up. We were driving out to the Butler Plank Road one afternoon, and were held up on an unaccustomed detour in Sharpsburg by a long freight-train. Both ends of the freight were out of sight. There seemed to be no reason why it should ever move. A line of automobiles stretching for blocks was waiting. Phineas, and I, with New England fatalism, composed ourselves for a long delay. But suddenly a big car in front of us spoke. The rest took up the chorus, until every machine in the neighborhood was honking at the top of its horn. A quarter of a mile of high-powered cars expressing indignation in hideous concert can do much. The freight-train parted in the middle and let us through.

Cars toot to express their opinion in all cities, to be sure, but when they try it in Boston, the police keep them waiting all the longer, for discipline. Boston believes that there is a principle involved: these spoiled petted motors of the rich need a lesson. But in Pittsburgh, where one really finds an ingrained reverence for material equipment, a Rolls-Royce and a Pierce-Arrow and a Packard and a Marmon coupe, all hooting in close harmony like a male quartette, can lead a chorus that will break the spirit of the most red-headed policeman west of the Alleghenies. It is a stimulating sight, if you are of those who enjoy riding over red tape. "Pittsburgh," says Phineas, "makes a dash where Boston would put a semicolon or period."

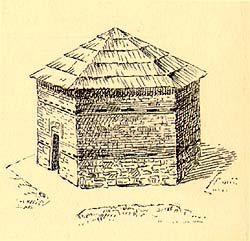

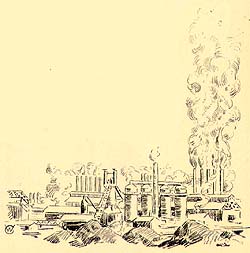

I wish that Pittsburgh had been named Fort Pitt, after the historical stronghold there. Fort Pitt exactly suits it, with its stockade of smoke-stacks, its "Block House," and the barricading ramparts of its hills. And as a second choice, I should name it Saint Pittsberg, for the sake of mixing up the nationalities and creeds. But Fort Pitt is better suited to its location. When Washington saw it, he wrote in his journal, "I spent some time in viewing the rivers and the land on the fork, which I think extremely well situated for a fort." It still is, with its wonderful smoke-screen all around it--smoke of all colors, not even predominantly black smoke, but snow-white and ochre-yellow and strangely tinted clouds of it--some from coke, some the dust from ore, much of it not smoke at all in the strict sense, but drifting along the rivers and lingering in the valleys where the wind can not scoop it up over the hills.

Looking down at this smoke-carnival from the top of a peak, one gets the impression that Pittsburgh is doing it on purpose, willfully puffing rings around itself out of the ground. Seen from the Aspinwall bridge at sunset, the smoke and the ore-dust take on the lightness of an Indian Summer haze. Seen from Bigelow Boulevard in an early winter twilight, it looks like a vast saltless sea of fog, with no lighthouse to pierce it except the huge illuminated "57" of the Heinz Works, and no foghorn except the whistles of the mills.

Knowing what hard work all of this means for somebody to keep it going, one feels guilty in perceiving any beauty here. But the fact remains that the floating shadows, and the indistinctness of outlines, and the deep wide spaces in which the smoke drifts and curls, all combine to form a marvelous screen for the play of lights and colors. There are Japanese effects in delicate monotones on winter afternoons; airy Claude Monet color-effects at dawn; Whistler bridges and blue twilights; and Turner fires on shadow at pouring time after dark. It is a study of changing mist and colors on vapor, with a background of still other layers of vapors and colors and mist. At least, this is what an eye with no housekeeping conscience might see, if social responsibility could be put to sleep. One of the steel manufacturers likes to take his friends to see one especial smoke that has a coloring which he describes as "Elsie DeWolfish"--a lovely hue of softest rose-color on a background of canary yellow and pale gray. Jusserand called Pittsburgh "the City of Magnificent Smokes."

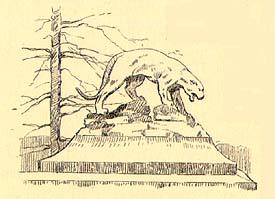

Nobody, I think, would claim that Pittsburgh is a dainty spot; but nobody can deny that it has (as tactful persons say of a homely friend) an "interesting expression." Every part of Pittsburgh has an expression of its own. One can no more expect the busy craggy sections of the city to take on the aspects of a pretty pastoral village than one would require the mastodon in the museum to preen itself like the flamingo. Pittsburgh is a mastodon, but it is a live one.

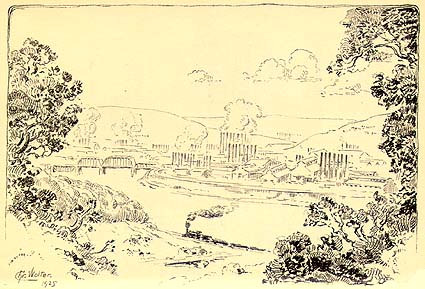

If I had a guest who had never seen the place, I would take him on a flying trip from East Liberty around the edges of Highland Park for a view of the industry on the Allegheny; then out on Beechwood Boulevard, for a glimpse of the steel works on the Monongahela; then down the Boulevard of the Allies and around to the Point, across the river to Mount Washington, back again around the Block House, through the downtown district and up Bigelow Boulevard to some choice spot where I would turn my guest loose and let him explore for himself. He would certainly get lost, but this would give him a chance to learn how the Pittsburgh streets run over and under each other, in a sort of basket-weave--here and there a triple layer vertically arranged like the weave in the sides of a bird's nest--some streets a whole hill beneath the ones that cross it, with the levels of society topographically arranged. Some one should invent a collapsible contour map of Pittsburgh, made on the principle of water-wings, so that you might keep it in your pocket until needed, and then blow it up to ascertain which streets lead to the brinks of impassable gulches and wild crevasses, and which to great cairns and to the blank walls of vertical precipices to the top of which only the airy railway of the hair-raising "incline" can ascend.

Pittsburgh is well aware of the perils it presents to strangers, and one of the guide-books observes comfortingly, "It is not intended to ask strangers to memorize all this. A mail-carrier and a policeman are presumed to be posted as to localities, especially the locality where met." Before I turn my friend loose in the city, I shall inform him that eight out of ten persons he meets will be strangers like himself, and that nothing short of a letter-carrier or a very alert small boy can be "presumed to be posted," even in the locality where met.

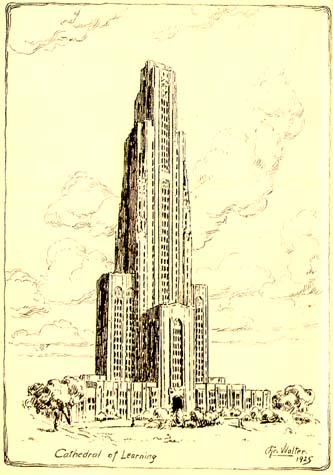

I shall ask him, too, to notice just one thing: that when Pittsburgh does anything on a colossal scale, it is colossal spelled as the Germans spell it, with a K--Kolossal. And finally, I shall take him away from the contemplation of the most colossal of smokestacks, and I shall let him listen to the music of the most colossal of organ-pipes, at a Heinroth recital on a Sunday afternoon, in the Carnegie Auditorium packed with men. Even at a recital, there is a vast majority of men.

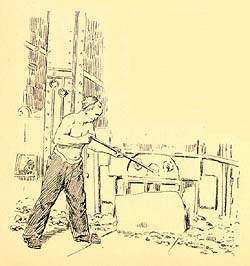

For Pittsburgh is above all the most masculine place in the world. It is more masculine than a mining-camp or a logging-settlement or a whaling-ship, because in those one finds only men's rough-hewn, knockabout, haphazard makeshifts, deliberately rude; whereas in Pittsburgh one sees their finished products, the product wrought out by the masterful, metal-conquering type of man, masterful in the sense that Barrie and the Scotch have in mind when they say "magerfu'."

This impression of Pittsburgh's exaggerated masculinity is strongest when you see it in two scales; first, in the magnified detailed view, as when you stand in the yard of one of the vast factories and look up at the tons of metal looming around; second, when you see it on a reduced scale, in a bird's-eye view, from Mount Washington or from Herron Hill. If you gaze down upon it from one of the highest peaks, it looks like a grand collection of mechanical toys--like the playthings you might see under a little millionaire boy's Christmas tree. Miles and miles of toy freight-trains, thousands of miniature automobiles running along the suspension bridges like little cashboxes on a wire, toy steamboats, meccano-bridges and towers, every sort of contrivance that can make a loud noise, or run very fast, or flash a bright light, or go puff-puff. Every city has some of these, but Pittsburgh has them all. And in most cities there are more toys intended expressly for little girls. No woman could have dreamed Pittsburgh, not even a Valkyr or a Borgia or any of the Gray Norns. No woman, if consulted, would have permitted Pittsburgh. We would have told it not to leave its toys all strewn around the pretty rivers over night.

I suppose I might not like Pittsburgh if my work took me too near a blast-furnace, or if I had to live in some parts of Turtle Creek. But flitting through it and perching there as I have, like the Pittsburgh owl, I cannot help admiring its solid industry and its tremendous usefulness, and its huge two hundred bridges, and the hearty way it has of being openly itself. It even names some of its streets after its scientific paraphernalia: Crucible Street and Saline, Theodolite Street, Furnace Way, Collier, Bessemer and Tripod Way. Any one would love its green locust trees, giant flowering almond-bushes, box-elders and sycamores; and the country round about with its clouds of peach-blossoms in the orchards and its big farms where one may keep a family coal-mine and oil-well along with one's chickens and one's bees. And there is no end to the exploring that can be done in the outlying regions where one finds places with such old-time names as Squaw Run, Moon Run, the North Star Post-Office, Ben Avon, Castle Shannon, Breakneck School, Old Plum Creek, Tomahawk, and Wind Gap.

Finally, to one who has recently been sojourning in a discreet, New England college town where a delegation of citizens lately petitioned that the traffic signs "Go Slow" should be amended to the more pleasing and grammatical phrase "Go Slowly." it is exhilarating to go whizzing around a hairpin curve just at the yawning brink of a Pittsburgh "run," and behold the following warning in large letters, succinct, uncorrected, and never, never by any chance obeyed--the categorical road-sign "SLO."

I have never heard my Pittsburgh owl again. I still hope to come upon him some evening, for I have seen a wild brown cotton-tail rabbit on the driveway at the Bureau of Mines and a bumblebee near the corner of Craig Street and Forbes. Moreover a Pittsburgh friend assures me that there has always been an owl's nest in the cornice of one of the neighboring churches, and another in the trees near the Negley Avenue Hill. She tells me that when she was walking home from a Paderewski concert at the Mosque one night, she herself saw three little screech-owls sitting in a row in the moonlight on a telegraph wire. I reported this news in high feather to Phineas, and he does not suspect that I ever entertained the slightest doubts about my own beloved owl. But in view of all that I had learned about the accomplishments of the motor traffic in good old Saint Pittsberg since we came, I confess that there were moments of horrible misgiving when I judged that my Pittsburgh owl might very possibly have been a truck.