Introduction.

World War II was the most horrendous calamity

to ever befall our kind. With over fifty million dead and tens of

millions more permanently physically or mentally scarred, this was the

defining event of the Twentieth Century. Fifty-five years after the

end of this war, people still living carry the scars of their wartime

experiences and many others have vivid memories of their lives

during these years.

Not all of the memories of this era were bad ones. It was a time of growth for the very young and a time of heavy labor for many of the working class.

What follows is the story of three people who lived during these war years.

Frank Gruda.

Age 86. Birth date: 5/20/1914.

Address: 1016 Laurel St. Bridgeville, PA 15017.

I was at the club across the street from our house playing pinochle when I heard about the bombing of Pearl Harbor. It was a Sunday evening and I was shocked.

I was 27 years old and working at the Flannery in Bridgeville where we made cannons. I was called up about one year later. I had approached the plant manager trying to get a deferment but that didn't work because I wasn't skilled labor.

Initial inprocessing for the military indicated the presence of a hernia which I had known about and it had caused me some difficulty in the past. I had two weeks prior to having to report for basic training and so went back to work. We were working seven days a week at that time.

I went to Michigan at the end of those two weeks for Navy basic training. The hernia was noted again there and I was scheduled for surgery, but I refused to have it done after hearing from some other guys that the surgery done there was poor quality with a long painful recovery. They couldn't make me have the surgery and that made me 4-F. An officer came to see me and I refused the surgery a second time. He said to me, "What would happen if everyone was like you?" I replied, "Well, there would be a lot of people like me."

They sent me home and I went back to work at the Flannery. The men called me the 4-Fer in a kidding kind of way. They didn't want to go either.

I had the hernia repaired two weeks after coming back home. Dr. Wagner did the surgery and the company paid for it.

After I came back from Michigan, I ran into a woman who asked me why I wasn't in the service since she had two boys in. I just told her that I'd go when called.

Women started showing up at the plant within four months of the start of the war. I was busy enough at my job that I didn't notice how well the women worked. Some of them had steady type jobs and others rotated around the plant.

The Flannery didn't cover deferments for any but the skilled workers and that's why there was so much overtime. I worked six days a week and sometimes double shifts. I worked in the drilling department making bolts for steam locomotives. The plant was subcontracting a lot of other work at that time other than just making guns.

I was tired a lot. Sometimes I'd hide from the supervisor for the last 15 to 20 minutes of the shift so that they wouldn't be able to get me for another shift.

I lived with my sister and brother-in-law in Heidelberg at this time. My brother-in-law drove us both to work. Rationing started right away. That included oil, gasoline, sugar, coffee, meat and cigarettes. Once a week they had a bucket full of packs of cigarettes covered with a cloth at work. The cloth was so that guys wouldn't be picking through to get their favorite brands. You got one pack a week. I didn't smoke but I'd get in line to get smokes for some of the other guys. The cigarettes were all off-brand varieties because they sent the Lucky Strikes and Camels to the guys doing the fighting.

The rationing didn't affect me because my sister got the sugar and coffee and I didn't have a car. It didn't seem that we had any the less of anything.

You could get shoes, but they weren't as good as those made prewar. I remember that shirts were poorly made and rubber tires were hard to get. The tires were rationed and there really weren't that many cars. Newspapers were readily available.

I had two brothers and two sisters. My cousin Albert was the only member of my family who went into the service and he wasn't in long. I don't recall why he was out so quickly. It was the Army that got him. The war didn't affect my family much. All it was was work. We all worked. We made more money than before the war, but we were all tired a lot. It seemed like the poor people did nothing but work so that they could have their war. Poor people don't have politics, you know. They just work. There's no time for anything else.

The best thing that happened to me during the war years was that I met Stella Cherosky in church and we got married on February 1, 1944. It was a small wedding. We moved to Hickman Street in Bridgeville and I was able to walk from there to work and then I'd get a ride home with another guy from the plant for a dime. Stella was 28 and I was 29 when we got married. Stella worked in the office at the Universal Steel Mill at that time.

I don't remember the stars in the windows that you mentioned. There couldn't have been many in our neighborhood. Not many went off to the war. One guy that I played soccer with was killed in action. They brought his body back. Another guy, a neighbor, lost the use of a hand in Germany. I do remember the A, B, and C stickers in the back car windows. I didn't volunteer for anything. There just wasn't any time for that. My people didn't do any recycling that I remember. I do know that cigarettes and meat were in short supply.

Stella had trouble getting decent stockings. Some of them had holes in them. She went to the movies at the theatre in Bridgeville and saw newsreels about the war.

I worked more with the war and had a brief brush with the military. Those years didn't really affect my life much. I didn't follow what was going on overseas that much. It was in the papers every day, but I was too busy to care. I worked six days a week and went to the club on Sundays, as that was my only day off.

I do remember hearing about the A-bomb and thinking that it wasn't a good thing. Too many innocent people had been killed, but I suppose that it was the only way to end the war.

Mary Harwick.

Age 65. Birth date: 1/14/35.

Address: 514 Clemson Dr. Pittsburgh, PA 15241.

I was at school when I first heard about Pearl Harbor. We had two grades in one room and it was my first year in school. My teacher, Mrs. Carrier said that Pearl Harbor was a very bad thing and we have to pray for those men and our country. Nothing was said at home. My parents may not have wanted to worry me.

Sonny Cable was the next-door neighbor who joined up. It was then that I realized that this was going to involve us. I was six years old and snow was on the ground. There was a going away party for Sonny. He survived the war without a scratch.

Dad had three kids and probably could have been deferred. I was the youngest. He was 37 and I think that they didn't draft after 38.

Life went on for the years 1941 to 1943. We moved in 1942 and I skipped second grade that year. We rented a house and shortly afterward, dad was called up. The landlord soon sold that house and we had to move across the street to another rental.

When he left us, we brought dad to the Pennsylvania Train Station. I was awed by all of the soldiers everywhere. I was daddy's little girl. My sister, Pat was 11 and Duane was 15. I realized at some point that my buddy was going to be gone and that was it. Mom didn't cry much but my sister and I sure did. Duane was stoic. He was a sports star. Dad wanted to make sure that he continued with sports and school.

Dad wrote regularly. He went to boot camp first and then on to engineering school at Granite City. His entry aptitude test scores were high and thus he could have gone to officers training. He opted out of that because he thought that he was too old for it at the age of 37. He turned 38 on the troop ship going to England.

He wrote every week to mom and then to each of us kids. When he got overseas, we wouldn't get any mail for awhile and then a bunch of letters would come at the same time. I really remember not knowing what was going on. All of the mail was censored then and the soldiers had to develop little tricks to let people know where they were. He was in England for awhile and then he got word to us that he was sent to Luxemburg. He sent me a handkerchief for my birthday from there with Luxemburg on it and that's how we knew where he was. It came in an airmail envelope.

We were poor and I got stomach pains one day. I was afraid to go to the hospital because we couldn't afford it. Dad sent all of his money home to us.

I remember walking down the street at that time and seeing the stars in the windows. They were on an eight by ten inch satin sheet. The stars were blue, but when someone was killed, they were changed to gold.

My most vivid memories are: 1) waiting for dad's letters; 2) the stars; 3) rationing; 4) war bonds.

The ration coupons were precious. When mom sent me to the store with one, I was told to guard it, and I did. Mom was a baker and sugar was precious. The government sent the coupons based on the number of people in the household. They gave you the right to buy goods. Coffee and sugar were the important things for us. We used those coupons at the A & P. We had a car, but didn't use it much so that gas was not a problem. Oleo appeared and you had to knead this yellow colored pill into this white blob for that. We always had enough to eat.Mom went to work and may have been cutting her food intake in favor of the kids. Mom became a clerk in a department store, Duane worked as a soda jerk in a pharmacy. He was 16 and he'd make me a sundae after church.

My eyes started to get bad and I worried about the cost of glasses. If I squinted hard enough, tears would come and I could see the blackboard through them. That worked until the teacher sent me to see the nurse. I got glasses.

Nothing spectacular was happening at this time. We were just maintaining. Dad was driving trucks to the Rhine. He drove convoy trucks to the front, unloaded, and came back for another load. The real risk was from German airplanes. His assistant driver was shot and killed by a sniper. He didn't stop driving when his assistant was killed.

Dad didn't smoke until he got into the Army. Smokers got to take breaks at boot camp and that was a good enough reason to start.

The savings bonds were called war bonds at that time and every Friday the kids would take any dimes that they could to school to buy stamps for their coupon books. When the books were filled, you would get a $25 savings bond. There were posters all over the school that read, "Uncle Sam needs you to buy war bonds." My brother, sister, and I didn't get many bonds. I had a few and Pat got more because she babysat. You had to pay half of the face value for the bond.

My 5th grade teacher was a guy who was 4-F and he was always angry. He paddled the boys with regularity and the school finally got rid of him.

The summer after Duane's junior year he was scouted by the Yankees. He signed with them and went to training camp. He played for a minor league team in New York, but that didn't last for long. He was only gone for three weeks. They sent him back saying that he needed time to develop. Because he signed with them, he needed a hardship waiver to play during his senior year of high school.

Dad came home in 1945. Both of my parents had worried that he'd be shipped to the Pacific. I was 10 ½ and it was in the fall of the year. We went to the train station to pick him up. When we got home, mom and dad went upstairs. I ran up and saw them in the hall in a passionate embrace. I suddenly looked at them in a new way. It was my first realization of them as a couple and I realized how much they had sacrificed.

Once dad came home, I didn't think about the war in the Pacific at all. He was quickly discharged and that was that.

Duane and his friends wanted to join up after graduation. Mom was fearful of this, but dad said that it was a good idea because there weren't any wars on the horizon. Duane became a paratrooper and went to Japan where he played baseball all over the country against armed forces teams.

During the war, I saw newsclips at the movies of convoys on their way overseas. Those and dad's letters were the only things that made it all real.

I don't recall any meat shortages. There were some air raid drills and there were block wardens on every street. On the A, B & C gas stickers, the police had A's, I think, and that meant that they could get more gas than people with the other stickers. We all collected scraps of various sorts. Mom made sure that the holidays stayed the same for us kids.

I do remember a song that we kids used to sing. It went:

Remember Pearl Harbor as we remember the Alamo. And we will always

remember how they fought and died for us. Remember Pearl Harbor and fight

on for victory.

Donald Richards.

Age 61. Birth date: 10/4/38.

Address: 460 Coolidge Ave. Pittsburgh, PA 15228.

My uncle John was a rifleman during the war and he was sent to France some time after the Normandy invasion. I was about five or six when he was sent there and we followed the war's progress in the newspapers every day.

My mother and father were both air raid wardens and they got advanced notice of when all of the practice alerts would be. We had a secure room that had black out curtains where you could turn on the lights. There were chairs and a radio in there and so you didn't have to sit in the dark and wait until the alert was over.

My parents would walk around the neighborhood looking for light leaks during these alerts. People could be fined for violations although warning preceded fines and I don't think that my parents ever fined anyone.

We lived at 12th and Andrew Streets in Munhall, which was four blocks from the Homestead Steel plant at the bottom of the hill. All of our lights had to be out and meanwhile the open hearth was blazing away. That didn't make much sense even to a young boy.

I would stay in the blackout room for 30 minutes to one hour at a time. The alerts started with a siren and it would also be announced on the radio, as was the all clear. I think that this happened simultaneously all over Pittsburgh. We had these alerts about once a month.

The whole process was scary because you thought that we might actually be bombed. None of us knew that the Germans couldn't fly this far. If you had to go to the bathroom during the blackout, we had to turn the lights out in our little room. My aunt and grandparents lived next door and they would come over to be with me at these times. We all lived in a big duplex.

There was a flag in the windows with a star on it if someone from that household was in the war. These were very common in Munhall and Homestead. I went to the movies every Saturday and we'd walk past the houses and look for the stars. We'd be real quiet going past the houses from which a soldier had died. The stars were blue with a red border on a white field. I went to the Stall and Elight theaters with my friends. We saw Zorro, Tom Mix, and Abbott and Costello as serials. Every week there was a new edition.

My grandparents had a star in their pantry window for my uncle John Wilson. He was my only close relative who went to the war. He was in until the war was over, but came home twice on leave. The first time that he came home was after basic. He walked up the alley in his uniform and I paid attention to him because of the uniform and then I recognized him. He had a three-day pass and then went to Norfolk. We took him to the P & LE railroad station to see him off. We had talked about his experiences at basic when he was home. He was quiet and didn't talk about his later experiences much.

My grandparents got letters from John and grandma would read them to all of us. My aunt Jean was John's sister and she and John continued living in the house after the war. Aunt Jean later threw out all of John's old uniforms.

I collected grease and papers for the war effort. I got bacon grease from my grandmothers, mom and dad, and the neighbors. Bacon and meat were rationed at this time. I took the papers and grease to the butcher shop in my red wagon and he would weigh it all and pay me about a dollar for each load. He put the grease in his cooler after he weighed it. It was enough money for the movies and some candy, but not too many of the kids did this. There really wasn't a lot of fat around because there was little meat available at the time.

Meat, sugar, and margarine were rationed. The margarine came in a plastic container along with a deep orange color pill, which was part of the container. You had to break the pill and knead it with the margarine to make it all butter colored. Pineapple and orange juice were also rationed. Our neighbor, the butcher, would tell us when meat was due to come in.

Gas was also rationed. There were A and B stickers issued for the gas which were black with a white letter and about two by three inches in size. These were pasted on the rear window like an inspection sticker to one side and on the side where the gas inlet was so that the service station attendant could see it.

My grandfather had a dark green 1937 four door Ford with a floor shift. He had an A sticker, but we all used public transportation and rarely used the car. Our neighbors wanted grandfather to let them siphon gas out of the car since he didn't use it much, but he wouldn't let them do it and that, of course, increased his popularity in the neighborhood.

Grandfather got his gas at the station on the corner of 24th Street and West Run Rd. That gas station is still there after all of these years.

My grandfather raised a lot of chickens. He sold eggs to the neighbors and I delivered them on Sundays. I went to Sunday school and then had breakfast with the folks prior to making the deliveries.

My most vivid memories are: 1) collecting the grease and papers; 2) rationing; 3) reading the papers and noting how little gains there were; 4) not knowing where Uncle John was.

We had five or six neighbors who had someone in the service. Among the neighbors, C. C. Finesse was in the Navy. Mr. Uhey was in the Army. C. P. T. Urinak was also in the Army; he had two boys who were younger than me. They all came back all right. Down the block some of the stars did change.

I liked pineapple juice. The milkman delivered it to us and grandma would then give him breakfast.

The Richards clan had relatives in England and we would send them packages to help them out. What was shipped was sent in the chicken's feed sacks.

I went to my grandmother's every Sunday and I was called there one day, which was unusual. My uncle Al was there, who was in the British Navy. He was my great uncle and he could open beer bottles with his teeth. He was on leave because his ship was on the east coast for repairs.

We bought our meat at Adrians Butcher Shop and I really didn't notice any shortages on the holidays. Our concerns at that time were for the people who were not there.

My grandfather and I would listen to baseball on his radio set. I would listen to the top 20 songs at home. We'd sit on the front porch on Sundays and the back porch the rest of the time listening to the music and news.

They would blow the open hearths at a certain time. I believe that it was at 12:00 AM, 2:00 AM, and 4:00 AM. Our house was closest to open hearth #7. The mills would blow a whistle when there was an accident.

Dad was late coming home one night. He commuted by streetcar and none of us knew where he was. He'd get off the streetcar at 8th and Andrew Streets and walk home from there. Well, he finally showed up a little drunk and with a whole ham over his shoulder. He had no idea where he had gotten the ham.

Dad was married to my mother, had me at home and mom was pregnant. Dad had bad eyes and worked at the Westinghouse Plant and thus had been deferred. Mom thought that he was safe from the war and that's why she got pregnant then. Well, dad got a draft notice, which really upset mom, but V-J Day came and he didn't have to go.

I remember the day that they dropped the atomic bomb on Japan; the sky color was different some how. It was almost pink. People thought that the sky was pink because of the A-Bomb. We didn't know anything about the bomb. We just thought that it was a really big bomb.

General MacArthur was always in the news. It was interesting reading about him, but as a kid, I didn't really connect the European war with the Japanese war. They were two different events.

When the war in Europe ended, everybody went to downstreet Homestead and they were all shaking each others' hands and celebrating. It was like the whole war was over.

Two things of note at that point in time were that I left this neighborhood with my parents right after the war was over and I stopped drinking pineapple juice the day the war ended. I don't care for it even now even after all of these years.

Conclusion.

These are the stories of three very different people. Frank Gruda was a

worker for whom the war years passed very quickly, quite simply because he

was almost constantly working. Work overshadowed everything else in his

life and also the events occurring elsewhere in the world. He quickly

tired of the entire war business and simply tended to what he had to do,

day-to-day. From the beginning, he did not feel that this was his war.

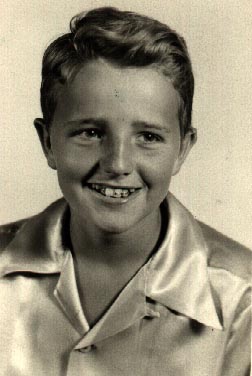

He was a poor man of whom no photographs exist from this period because as

he said, "They were an expensive luxury for people like me." Frank was

probably typical of millions of other men and women around this nation at

that time.

My other two participants in this project were both young children who had the good fortune of being able to observe the panorama before them as they grew. They were little sponges who took it all in and remembered it very well. They were not overburdened with work as Frank Gruda was and thus their interest was not quickly dulled. They both had family members directly involved and this heightened their interest even more.

All three of these storytellers provided rich insights in their personal histories of the war years. As is so often true, however, the youngest tell the most vivid stories of all.