To know what Pittsburgh is really like at Christmas-time, you should be at least eight different persons besides yourself, each with a separate geography and point of view.

First, you should be the traffic officer at the corner of Liberty and Sixth, near Penn, with 'The Store Ahead' at the right of you, the 'Five and Ten' at the left of you, and the cross-town cars shuttling past you, at the very vortex where the parcel-bearing shoppers from Squirrel Hill and Soho, Shadyside, Mars, and the Panhandle all convene.

Second, you should be an employee of the Heinz Works, down in the Allegheny Valley, rushing out the Christmas Special assortments under the sign of the '57,' spurred on by the motto of Mr. H. J. Heinz: 'To do a common thing uncommonly well brings success.' You should go home, if possible, up the weird air-way of the 'incline,' in the little sliding car that looks, by night, like a belated Toonerville Trolley steering for the sky.

Third, you must be a member of the Hungry Club, the Chamber of Commerce, or the Duquesne Club, with an interest in the Mosque, and a steel-mill on your hands.

Fourth, be a Westinghouse man, rattling out over Electric Avenue to East Pittsburgh or Turtle Creek in the gray dawn. Your children will exact of you that you bring them strings and strings of brightly colored bulbs to light the Christmas tree.

Fifth, you are a houseboat dweller afloat on the river at the Point. Your only neighbors are other houseboats, and you are wise in the lore of the three great inland rivers, especially at flood-time, when you see the whole Point going about in boats, up as far as the high-water mark at Joseph Horne's. To reach your smoke-stack chimney there should be an aquatic Santa Claus chugging up the river, like the steamboat Homer Smith.

Sixth, you should live at the top of one of the city's unexpected crags, with a precipice under your back veranda, and a landslide imminent at any time. In moments of anxiety you recall the famous verdict of the world's most notable engineer, called in to prescribe remedies for Pittsburgh's shifting landscape: 'Let it slide.' As soon as the fourth dimension is a little more clearly understood, Pittsburgh will build some houses over its edge.

Seventh, go out and live near Little Pine Creek, or Squaw Run, or somewhere on the Fox Chapel Road. Your driveway may be made of solid coal. At least you should have an oil-well, like an informal model of the Eiffel Tower, in your back yard. Your orchards are a dream of peach-bloom in the spring, but now only the cotton-tail rabbits are hopping there, looking for frosty buds.

Eighth, you are one of Pittsburgh's floating population, here without your family, a lonesome fellow going busily about with no Christmas chimney but your pipe.

These eight, combined with your present self, would give a general idea. But we could all think of others: a gate-man at the 'Pennsy'--or a choir-boy singing carols--or a member of the Kiltie Band at Carnegie Tech, with memories of how, after the game with Pitt, some excitable persons rushed into Schenley Park and removed the trident from the statue of Neptune by the pond--or an alumnus of Pitt, with pledges for the sky-scraper Cathedral of Learning, and memories of how, after the game with Tech some excitable persons rushed into Schenley Park and removed Black Hawk's nose.

Certainly among this list would be one real 'Old Pittsburgher,' a title that cannot be won in a lifetime, but must come down as an heirloom from one's clan, along with traditions of the days when Alexander Negley had his homestead and pastures at Highland Park, when Panther Hollow was really panther hollow, when Schenley Farms were really farms, and Shady Avenue still was Shady Lane;--of days before Stephen Foster wrote 'Suwanee Ribber,' when the Southern planters used to come in their luxurious boats up the Ohio and sit in the windows of the old Monongahela House to watch the river-traffic going by. Your family should remember when Langley was over at the observatory, when 'Uncle John Brasher' was grinding his first lens, and when Andrew Carnegie was a Western Union Telegraph messenger-boy.

Whatever interest in Pittsburgh's history you adequately represent, you are not lazy; and therefore you have won your right to share in the Christmas cheer.

There is a Pittsburgh story of two manufacturers who were sizing up a friend. 'Is he,' asked one of them, 'a go-getter?'

'No,' mused the other; 'he's a have-it-brunger!'--a subtly different, and, one surmises, a very much higher-salaried thing.

That Pittsburgh is largely made up of these two orders of men is never more evident than on the day before Christmas, downtown, when all the go-getters are cheerfully doing so in nimble hordes, while large delivery-wagons, careening with overload, are whisking parcels to the homes of the have-it-brungers, at a speed that brings to mind the recent Pittsburgh newspaper item: 'Car going up Fifth Avenue at seventy miles an hour cuts down a tree.'

In the midst of such a crowd, on the day before Christmas, I was downtown for a simple errand at the bank. The revolving door of the mammoth banking-house was whirling steadily, kept spinning without a pause by the stream of customers, like the paddle-wheel on a boat. Placards were already up advising us to join next year's Christmas Club, and every teller's window had its queue. A little apart, outside of any waiting-line, sorting some documents, stood a business-like individual who had once been pointed out to me as the employer of ten thousand men. At the teller's window far ahead in line, a tall young workman briefly despatched his business, turned to go, recognized his employer, and bowed. In response, the Iron-master nodded cordially, and spoke.

'I hope you'll have a very merry Christmas,' said he.

'I hope you have the same, sir,' said the burly young fellow as he went striding toward the door.

'Thank you,' his employer called after him; 'I'll have it, don't you worry, with my girls coming home!'

The workman turned and looked back, a fine Scotch-Irish twinkle in his eyes, and over the heads of the crowd the two men exchanged a brief but entirely satisfactory grin. It was not Capital interviewing Labor at the barred window of a bank. It was not even a go-getter confronting a have-it-brunger on the outskirts of a queue. It was one man to another, at Christmas-time--and the girls coming home.

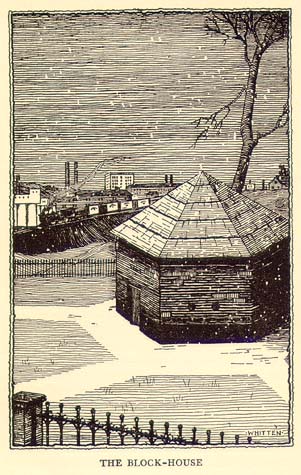

It seemed quite like the town to me, this touch-and-go conversation that I chanced to hear, and like the season as well. Outside the bank the holiday spirit was all abroad. I had done my shopping early and had time to see it all--the piles of holly and mistletoe and poinsettia everywhere at the venders' stalls, the animated toys in fairy-story groupings in the windows, the Christmas tree among the graves in Trinity's yard. I paused to read once more some of the good old names on the worn headstones, including that of the last of the Indian village chiefs, Red Pole, so decorously buried there among the early city fathers, with a wintry little forsythia bush growing near his grave. Swept for the moment into a history-loving mood, I decided to see what Pittsburgh's colonial landmark, the Block-House, was like at Christmas-time.

Down to the Point I trudged, and into the Block-House yard, with its bronze record of the exploits of the Black Watch. I went inside the tiny weather-beaten fort, under the old inscription to 'Coll. Boquet,' and climbed the stout little staircase and peered out through the gunholes at Mount Washington looming up across the river, gray with cascades of ice. Dutifully I repeated to myself George Washington's famous verdict when he gazed in his young surveying days upon this scene: 'A settlement built here is bound to grow and flourish beyond the imagination of men.' And as I gazed, a familiar legend on the mountain-side met my eye, an advertisement for apple-butter, appropriately Pennsylvanian, commanding the whole side-hill. I remembered a charming old lady from the outlying hills who said to me when I first arrived in Pittsburgh, 'You have come now, my dear, to live in the region of the butters.' And I found it true, apple-butter, peach-butter, made in immense kettles and stirred under the trees, the spiciest in the world. Pittsburgh is justly famous for its refreshments of all kinds.

But the Block-House was not especially in holiday mood, so I went down to the bridge to watch a 'tow' going down the Ohio, its broad flotilla looking life a flat, square, black island going downstream, powdered with sleet, its tugboat working busily through the scattered cakes of ice. Traffic on the bridge was thick. An errand-boy sped by me with a doll-house under his arm, and a loaded truck with a waving placard, 'Fancy young tom and hen turkeys for sale,' went flying past. Back I went, along the water-front, pausing to explore some of the little streets. The horses of an 'A. R. Co.' wagon had Christmas greens at their ears. A Ford truck without any radiator-cap had a bunch of holly and mistletoe stuck into the radiator where the cap should have been--a new placing for the bud-vase on one's car. A shipment of Flexible Fliers had just come in. The only spot that seemed not to have caught even a hint of Christmas cheer was the building where they have Missouri Mules for sale, Mine-Mules, Matched Mules, waiting in their stalls. I glanced in, and was tempted to toss a sprig of holly among their fair large ears. But there are rules of etiquette both for Mules and Men, especially if one is not a man and the mules are from Missouri, so I went on.

Around the corner near Water Street I saw a crowd of little children, and I paused. They were outside the Toy Mission, looking in.

'What time does it open?' I asked of one little boy.

'It's open now,' said he. 'Your card tells you when you can go in. Didn't you had your card?' He showed me his. 'Didn't you had any?' he repeated in surprise.

'No,' I admitted.

'Well, you will,' he assured me kindly. 'It'll tell you when to come.'

This utter confidence in the thoroughness of the card-system warmed my heart, as I went along home on the crowded car, up past the Carnegie Institute where Shakespeare's statue sat outside, attentively reading a large bronze book. Some mischievous student had climbed up his colossal knee and with neat crayon letters had entitled the folio he was reading, 'Life.' Not so bad, for Shakespeare. It was beginning to snow a little, and there was a rift of snowflakes on his sleeve; snowflakes too on the boughs of the globe-hung Christmas trees that stood on the lawns of nearly all the churches on the way.

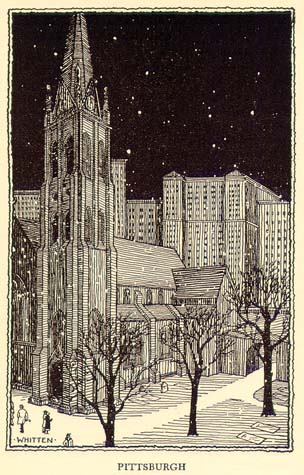

For Christmas in Pittsburgh is not all crowds and rush. Like any city it has its home-celebrations and churchly festivals, its carols and trumpeters and choral-clubs and organ-music; and even, if you were down at old Saint Patrick's, special ceremonies with Holy Water brought from France, blessed by Our Lady of Lourdes.

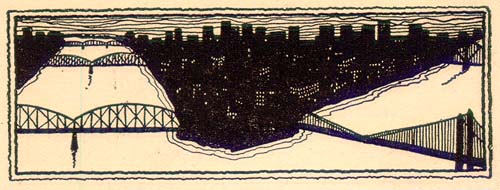

Late on Christmas afternoon we went out to walk around the reservoirs at Highland Park. It had snowed all night, and the park was drifted deep. White Christmas in Pittsburgh! The Allegheny River was a gleam of silver, and the coming twilight was beginning to shadow the Aspinwall Hills. A small river-boat, perhaps the Twilight or the Carbon, was just above the canal. Down the river as far as we could see were ice and snow and drifts of smoke at sun-down, a craggy landscape the color of an icicle against pearl-lighted mists of gray.

We drove back, circling among familiar streets, to see the new sleds drawn up on porches, the few late coasters taking one last slide, and the snow on the roofs of the fascinating little play-houses, just large enough for a family of dolls and their small owner, tiny dwellings built as Christmas presents in other years for certain little girls. They looked so sedate, thatched with snow and fringed with icicles, these small houses with real doors and windows--one, I knew, with a real cook-stove inside and real pans and kettles, one an early-Victorian villa, one a miniature city-dwelling with an actual mansard roof. It makes a city cozy to have such fairy houses beside the big ones on the lawns of thoroughfares as considerable as Forbes and Ellsworth, Pembroke, Negley, and Fifth.

As we turned toward home, the trees in all the windows of the town were being lighted. Probably Pittsburgh of all places is most expert about its Christmas lights. The curtains were drawn apart, and the trees stood in the windows, a gay twinkling of crystal on evergreen, and sparkling stars of light. They would be there every evening, we knew, of holiday week, until it came time for the whistles to blow the old year out.

And that, the ending of the old year, is the most distinctive of all the Pittsburgh customs. At midnight, instead of bells, the whistles blow. It is worth staying awake to hear them start. First one, then others, then many, with the casual rhythm at first of monstrous frogs around a pond. Then more join in, and the rhythm is lost in the growing volume of the sound, and finally all the whistles are going, all of them, the great bull-throated whistles, and the shrill ones, the deep ones, and those in minor key; whistles from Homestead, Swissvale, and the South Hills, forests of them, all up and down the banks of Monongahela and Allegheny and the Ohio, from the crucibles and tube-works and mills and glass-works, from the furnaces Matilda, Eliza, Hilda, Lucy, Isabella, and all the rest, for miles and miles. There are incredibly many of them, steadily blowing, not hooting, but simply blowing and blowing full-voiced for minutes on end, until they blend themselves into one huge wind- instrument, droning like a cosmic bagpipe all around town. It is far beyond pandemonium, far beyond chaos. It sounds mysterious to the ear, much as the universal glow of flaring red on the midnight clouds at pouring time looks ominous to the eye. There is something unearthly and mystical about it, involving the upper air. Persisted in, as they do persist in it, so long in the dark night, it is a tone that utterly drowns the comprehension, simply and absolutely unique. It humbles the imagination, and greatly disquiets the soul.

O Pittsburgh, oh huge, doing the heaviest work of the world in such an unceasing and enormous way, Happy New Year, for you deserve it. You have worked. There is a questioning note in your wild bagpipe music as you blow the old year out. Every one knows that you have giant questions to ask, and nobody knows the answer. But your problems are worthy of your steel.

Transcribed by Amanda Burrows.