The story of the parks system

surrounding Pittsburgh

operated by the Allegheny County Department of Parks, Recreation and

Conservation.

When William H. Seward, the United States Secretary of State, arranged to buy Alaska from the Russians in 1867 many Americans derided "Seward's icebox" as a colossal mistake. "Seward's folly," as it was also called, is today one of the most valuable natural resources the United States has.

The National Parks of the United States were also created against a background of complaint, yet today our great scenic national parks are endangered by overuse. The debate continues now over the proper use of mineral rights, or over dilemmas such as whether helicopters and airplanes constantly touring through the Grand Canyon spoil the serenity of the canyon for everyone else.

Allegheny County in southwestern Pennsylvania today has one of the outstanding county parks systems in the nation, but in the 1920s, North and South Parks were created, and later in the 1960s, when the regional parks were added, county officials faced the hard decisions and turmoil that all visionaries of public lands must confront. In the 1920s Pittsburghers had only to look as far as East Liberty to see farmland. People could walk from their houses to go hiking, or even hunting in the woods. Why then should Allegheny County buy thousands of acres of farmland north and south of the city for "parks"?

Yet within thirty years North and South Parks were so heavily used by the public that county commissioner Howard Stewart envisioned the need of an additional regional county parks system. By the 1960s Stewart feared all large tracts of land would be claimed by industries or suburban developers, and the general population would have no additional recreational space. Again opposition could be heard--Why ring the city of Pittsburgh with county parks when you had city parks like Schenley and Highland and Frick and Riverview, and county parks like North and South, and a state property like Point State Park? But long-range planning won out, and a set of regional parks was created for the public, and Howard Stewart was proven to be right. Today if you tried to find 1000 acres of land in Allegheny County to create a new park, the land would be either unaffordable or impossible to gather.

Here then is the story of the Allegheny County parks systems--now operated by the Department of Parks, Recreation and Conservation. This network of nine parks, comprising nearly 12,000 acres of beautifully landscaped fields and woods, is one reason why the quality of life in Pittsburgh and its neighboring towns and cities is so attractive. Yet this story has been hard to understand. Most residents of the county are unaware of the entire network, although they might delight in the local county park. In addition, the distinctions between city, township, county, state and federal parks are easily lost sight of. Pittsburgh city parks serve the city residents very well...but in Allegheny County the county system impacts the greatest numbers. One estimate is that on a pleasant Saturday or Sunday in the summer, some 200,000 people can be found in North and South Parks alone--nearly half the population of Pittsburgh. The county system emerged slowly in the two periods of growth between 1927-31, and 1958-79. It has been a long, evolutionary tale, hard to see, and for that reason largely untold.

The People's Country Clubs 1927-31

In the 1920s a tide of industrialization swept the Greater Pittsburgh area, and rapid urbanization began to show itself in the rural communities surrounding the business districts of Allegheny County. One county commissioner, Edward V. Babcock, urged the preservation of rural lands in their natural states. His idea, for a two-part system in the north and south regions of the county, became the basis for the system which developed between 1927 through 1931. Babcock actually purchased land for the parks which he then turned over to the county at cost--a procedure which was to be repeated later when the regional parks were assembled. The Department of Parks was organized on April 14, 1927, in Babcock's phrasing, for "the purpose of establishing, making, enlarging, extending, operating and maintaining public parks within the county and for enforcing rules and regulations established by the county for patrons."

Controversy immediately surfaced about the financing of the parks as County Controller Charles McGovern, in an election year in which he was running for county commissioner, challenged the appointed commissioners' selling bonds to cover the purchase of the land. In 1927 allegations and investigations piled up, and Controller Charles McGovern did succeed in being elected a County Commissioner after running on a "no frills-no deals" campaign.

But despite the political changes that always affect county policy towards the parks, the physical building blocks for the parks were laid by 1928.

It is important to remember that in 1927 the farmlands destined to become parks were not the woodlands and picnic groves we see today. The "people's country clubs," as the parks were called, had to be physically created. The forests of the 1980s are the result of reforestation programs begun as early as 1927. Native trees were used, the maples, the oaks, the beeches, mixed with dogwoods, cherry trees, and pear trees to create color in the springtime, and fragrances.

Behind much of the landscaping was the thinking of the talented Paul B. Riis, who was recruited in 1927 from the Rockford, Illinois, Parks. Riis had worked within the national park system, which was also close to its infancy in those days. He had helped develop Yellowstone and other national parks, creating stone lodges and other amenities, and now he was being paid the princely sum of $7,200 per year (a high salary much debated by county officials) to lay the groundwork for North and South Parks. Many of his efforts--the major landscaping, the road systems, the golf courses, North Park Lake--are enjoyed by the public today.

Director Riis inventoried the resources available on the site--the lumber, logs, the native stone for quarrying--and set up construction businesses to build the parks. They transplanted, reforested, repruned the trees. Much work was done by the youth conservation corps, and the CCC Camps, by people trained to develop public recreational facilities. He also advised on the acquisition of new land, and helped enlarge the system, as his successors have done.

The philosophy of recreation in the '20s and '30s was different than it is today. The differences between the haves and the have-nots of society was understood differently, and the county parks were called "the people's country clubs," bringing to poorer people the same recreation that the wealthy paid for at private clubs: golf, tennis, swimming, picnicking. The parks offered common folk the chance to escape to rural campgrounds, day camps, and "retreats." Certain modern recreational concepts had not yet arrived: people didn't "swim," they "bathed"; hence, a large South Park pool was only four feet deep at its deepest point.

The depression which ravaged the United States in 1929 had an effect upon county income, and depleted the Labor Fund for county employees' salaries, causing hardships for employees and their families. Then, in the summer of 1930, "the great drought" scorched Allegheny County as no rain fell between June 15 and the last week of October. Many park projects were delayed because of the water shortage, including the opening of the golf courses. In North Park, Pine Creek ran dry, and another source of water had to be found. Two permanent wells were eventually established to supply the park with water.

By 1931 North and South Parks were in the last phase of their early development: additional bridal trails, nature trails, and groves, more horseshoe courts, ball diamonds and tennis courts. North Park received additional parcels of land and developed a beaver meadow, a bird sanctuary and a primitive trail.

The Olive Miller Homestead in South Park has remained a site of genuine historic significance. Near that location in 1794 the first shots of the famous whiskey rebellion were fired. Oliver Miller's original log house received a stone addition by his son James in 1808, and in 1830 a second stone addition replaced the original log house.

Additions to the park accumulated in various ways. The Joyce Kilmer Memorial, named after the poet who wrote "Trees" and who was killed in World War I, was dedicated in 1934; the prominent local architect Henry Hornbostel designed it. The memorial is on "Corrigan Drive," which was named after the famous "Wrong Way Corrigan" who, in order to challenge the rules of planning flights, deliberately flew from Brooklyn to Dublin in 1938, instead of from Brooklyn to California. Also in South Park is a totem pole carved by an Indian chief and his son in 1938; they had been brought to the city to promote ball games for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

North Park, at 3010 acres, is the largest park in the system, more than 1000 acres greater than its sister facility, South Park. There are dimensions worth noting about the waters of North Park. The lake is the largest man-made body of water in Allegheny County, flowing over 75 acres, and is bordered by four and one-half miles of natural woodlands. The swimming pool in North Park was once considered the largest in the world; it holds two and a half million gallons of water (compared to say 20-30,000 gallons in a modern city pool). In the '30s and '40s, before pools proliferated in homes and private organizations, the monstrous North Park Pool seemed a logical response to the "bathing" needs of everyone north of Pittsburgh. A large South Park pool was also created, and the two pools, the only major swimming facilities in the county, attracted some 300-500,000 people per season during their first two decades.

The idea of North Park Lake, and of fishing in the lake, was advanced by County Commissioner John J. Kane. When the Old Pine Creek flowing into a marshy area was eventually transformed into a lake, the notion of stocking the lake with fish naturally followed. Some 50,000 people bordered the well stocked lake on the first day of fishing in 1937, and KDKA broadcast the ceremony as Commissioner Kane tossed the first line into the waters.

Indians as Curators -- A Failed Romantic Idea

In those early experimental days it seemed obvious that parks should have wild animals, and that the ideal caretakers or curators of wildlife would be real Indians. And so the county commissioners brought two tribes of Indians from a Montana reservation to live in the parks. Chief Big Beaver and his tribe went to North Park, and Chief Wild Eagle and his tribe went to South Park to tend the animals delivered there in 1927.

This was no small affair. Thirty-six head of buffalo were trucked in by means of a motor caravan, led by a tank. Reporters followed in private cars. Deer and other native wildlife from Pennsylvania were also provided as part of the Indians' herd. But the gesture ended badly. The Plains Indians found the winters here too severe, and left after one season. In North Park, the Indian "curators" of the herd did not so much protect it as use it the way their ancestors would have--for food and clothing. They were asked to leave. The romance of the American Indian could not survive in a county park.

More Improvements

In December of 1928 plans were made to build outstanding golf courses at both North and South Parks. Spacious and well-planned, the golf courses were an immediate success. One golf pro called South Park Golf Course "a beautiful, natural layout that is worthy of a national championship."

Jens Jensen, a Chicago landscape architect experienced in building pools for West Park in Chicago and for private clients such as Henry Ford, made a survey of locations for four more pools in South Park. When Director Riis chose Jensen to actually construct the pools, another controversy developed over the use of local architectural talent--there were 126 architectural firms in Pittsburgh at that time. Eventually South Park got a wading pool, a large shallow pool (375' long, 150' wide, 39" deep), a circular splash pool for shallow diving, and a large deep pool. The large pools each contained 800,000 gallons of water, and were designed to hold 15,000 people a day.

The bath-house for the swimming pools was patterned after the Old Stone Manse, the home of the famous insurrectionist Oliver Miller during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, but was designed with the latest facilities to accommodate 3,000 people at a time.

The year 1929 saw many changes in the parks, including 35 new picnic groves, 14 dance pavilions, and the installation of oven shelters in many of the groves. Constructed of native stone, the oven shelters allowed cooking during the winters, and after sunset; square hearths for corn roasting were added to the ovens. Nature and bridal trails were opened at each of the parks, winding in and around hills, high ridges, woodlands and open glades: six miles in North Park and three miles in South Park. Along the nature trails, which were designed for educational value, were specimens of living and mounted wild life.

The County Fair in South Park

In the 1930s South Park came to be used as a county fairgrounds, requiring expensive development: grandstands, racetracks, and support buildings. At that time there was great interest in county fairs, and the county had many more farms, ample produce and livestock, and a larger rural population. The County Fair was the big event of the summer, and for more than thirty years attracted an estimated half million people each season.

But by the later '60s farming in the county had declined dramatically, and rival entertainment activities were everywhere. Gradually livestock and produce had to be brought in from neighboring counties, and the 4H people had to extend their invitations beyond the county. The county fair changed into an industrial exposition as well, showing off the latest in U. S. Steel technology, the newest aluminum making process from Alcoa, or a model of the latest boat built by Dravo. People were interested in industrial products--everything from aluminum screen doors and sashes to continuous casting methods--and the agricultural side of the fair faded away.

In addition, new outlets developed to witness special activities such as little league baseball, high school sports, and competitions of high school bands and drill teams. Instead of saving up for the big county fair event, the sports teams travelled within newly developed leagues, and the bands toured at apple and cherry blossom festivals in other parts of the country.

South Park fairgrounds are intersected by major state highways, at one time a simple advantage in bringing people to the parks, but now those highways have attracted homes and businesses, and the park cannot be isolated any more. The Allegheny County Fair was free, and all the grassy meadows and fields were used for parking. Today county fairs charge for admission, for parking, for grandstand events--the old days of free access and parking are gone.

South Park is in the most heavily populated portion of the county outside of Pittsburgh, and is used by all levels of the community. Few special events need to be scheduled there any more to attract people--although the old fairgrounds are still rented to organizations. Antique and collectible shows bring in hundreds of dealers for one event. Or a softball tournament will be given in which several games can be played at one time. Larger businesses and corporations like to rent the space for the company picnic.

Among the changes at South Park is the installation of a wave pool, replacing the old bathing pool, which needed constant repair. The popular wave pools, found also at Boyce and Settler's Cabin Parks, each attract about 100,000 swimmers per season, usually from the last week in June through the middle of August. The school calendar gives children a chance to swim by mid-June (often the weather is not cooperative even then), and by mid-August the schools are starting up again. College students are going back; football and band camps are underway. Mid-August is the time to go swimming in the county pools if you like to avoid the crowds.

The Regional Parks

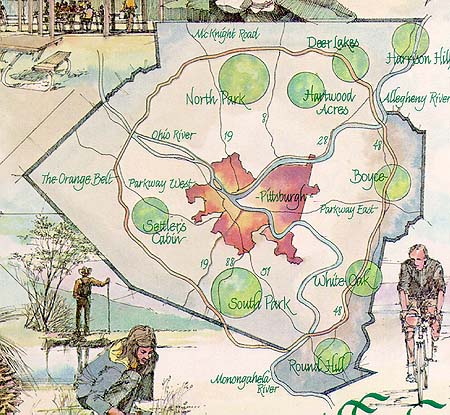

Allegheny County today has seven regional parks in addition to the great North and South Parks that are now nearly 70 years old. The regional parks ring the City of Pittsburgh along the highway route of the Orange Belt, at a radius of about 15 miles from downtown. No county resident is more than a 20-30 minute drive from a county park.

By 1958, when Pittsburgh was engaged in its first Renaissance, and foundations were already in place to help improve the quality of life in the region, plans were underway for acquiring a new system of regional parks. The Allegheny Conference on Community Development, a privately endowed citizen's group for community action, carried out a county-wide survey of potential park locations. The next step was to take the results of that study to foundations which would aid in acquiring land for the public benefit. Specifically, help was obtained from The A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, The Richard King Mellon Foundation, and the Sarah Scaife Foundation. Here as in so many other instances, one sees the crucial role that Pittsburgh foundations have had in shaping a better future for the Pittsburgh region.

The Mellon Foundation purchased the land privately, and then offered the county 3,650 acres at six desirable sites. The cost of $2,750,000 was the at-cost price, which the county paid off in installments. A bond issue of $4,700,000 was floated by the county to obtain the property, make additional purchases, and begin the surveys and develop the sites. It is unlikely that park lands will ever again be bought with the sorts of federal and Commonwealth 90 percent subsidies, plus half the closing costs on purchases, that were used to acquire the regional parks.

The County Commissioners in 1958 moved swiftly and appointed as Director George E. Kelly, an experienced parks administrator, with the commission to develop a series of six parks. George R. Kemp, a trained forester and civil engineer, supervised work in the field and administered the planning effort.

The Department of Regional Parks created in 1958 was separate from the original Bureau of Parks created in 1927. But by 1969 both these groups merged, along with other departmental groups responsible for related interests such as the county fair and recreation, to form the current Department of Parks, Recreation and Conservation.

The ingenious and yet conservative plan by which six parks were developed (more about the seventh park, Hartwood, later) involved the collaboration of three different firms of landscape architects: Griswold, Winters and Swain; Ezra C. Stiles and Simonds and Simonds. Each office was assigned two parks and asked to prepare land use studies, master control plans, preliminary development plans, construction plans, and specifications. But the three firms worked together as a team in familiarizing themselves with all the park lands under development and in commenting on each others' planning.

The consulting firms visited some of the best regional parks in the nation to analyze their success: Chicago and the Cook County Forest Preserve; the regional parks of Akron; and the Emerald Necklace System of Cleveland. One piece of advice they received from the General Superintendent of the Cook County Forest Preserve District, Charles G. Sauer, was, "As to population studies, forget them. Buy all the land you can and you still won't have nearly enough."

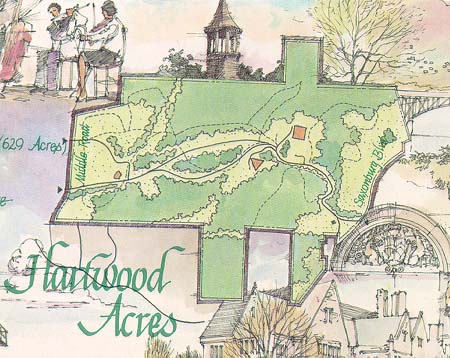

What is a regional county park? It is one of a series of inter-related parks, located at strategic sites throughout the county, designed to serve the public by making the best use of its environmental potential. Standardized equipment, and eventually maintenance through a central county department rather than through individual park units, makes for economical operation. But at the same time each park is individually designed to take full advantage of natural landscape opportunities such as streams, rock outcrops waterfalls, native groves, broad meadows, natural forest cover, and steep hillsides. The system in all of its variety should provide an unusually satisfying whole. Above all there should not be duplication, park-by-park, of the same monotonous groupings of pools, golf courses, and too-numerous shelters. These parks were originally conceived not as playgrounds for local residents so much as leisure time retreats, free from city influences and complete with facilities for simple family-type recreation. Experience with other regional parks in the nation suggested that l000 acres was a minimum: smaller parks receive such heavy usage that they become unattractive and require heroic efforts to maintain. But special considerations, like the opportunity to obtain Hartwood (629 acres) or the spectacular site at Harrison Hills (500 acres) also come into play.

With these ideas in mind, the architectural consultants produced basic guidelines for a regional park: low maintenance conservation areas suitable for simple outdoor educational and recreational activities, good roads, ample parking areas, scattered picnic tables and grills, simple but substantial shelters and toilets, and recreation meadows. Park boundaries were to follow existing road and highway patterns, or rivers and railroads--physical lines of demarcation. The team approach of the landscape consultants worked extremely well in this project, producing a whole that was greater than the individual parts, according to an article in Landscape Architecture entitled "The Birth of a Regional Park System" (April, 1963).

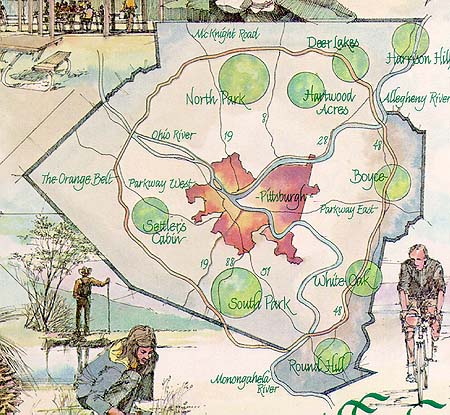

Boyce

First of the regional parks to be dedicated, in 1963, was William D. Boyce Park, honoring the founder of the Boy Scouts who was born in the area. All the picnic groves and shelters have names with Boy Scout associations: Tenderfoot, Eagle, Den, and even Baden Powell (the founder of the British Boy Scouts). Boyce serves the populous eastern region beyond Monroeville, and has been outfitted with major recreational features. It is the only location for downhill skiing in the county, with ski lifts, a lodge, and all the amenities. There is a large ski lodge called "Four Seasons," a large recreational complex, and a wave pool. Allegheny County Community College occupies part of the original park property, which was exchanged for adjacent land farther removed from major highways, upon which the wave pool was built.

As much as half of the park is still undeveloped, but long-range plans call for the restoration of the Carpenter homestead--a log house, spring house and barn--and an interpretive center on the life of the pioneers.

In 1976 anthropologists associated with Carnegie Museum of Natural History excavated the site upon which the recreational complex was to be built. The findings included artifacts and some 26 burial sites, and suggested that a village of the Monongahela people occupied the site in the 14th century AD.

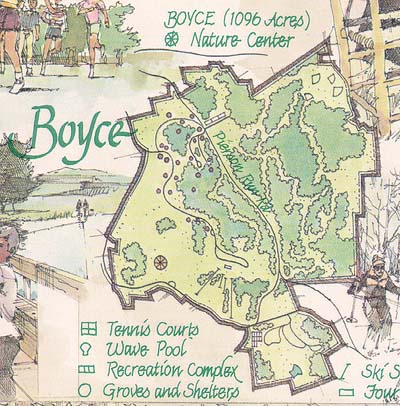

Round Hill

At Round Hill Park in Elizabeth township in the southeast corner of the county there is a modern working farm that supplements the park itself. The exhibit farm is open every day of the year and affords tens of thousands of school students on field trips, and daily visitors, an interpretive program that revolves around the farm, and the water and food cycles of life. The 17 picnic groves reflect the life of a farm with names like Alfalfa, Timothy, Wagon Wheel and Quiet Acres.

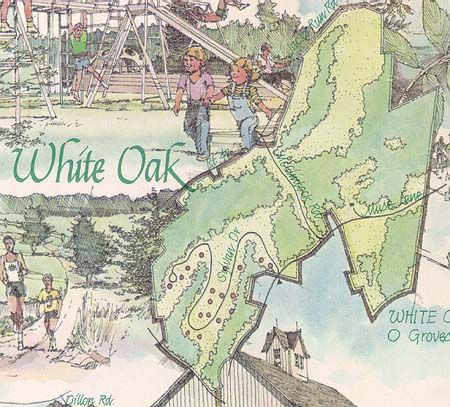

White Oak

In White Oak Park near McKeesport there are plants that exist nowhere else in the state. Trillium, wildflowers and particular types of groundcover have attracted the attention of botanists, and the western border of the park is rugged steep hillside that only the most adventurous hikers spend time on. Some of the stands of trees are primeval. The picnic groves have tree names such as Mountain Ash, Juniper, Beech, and Sumac.

Originally White Oak Park was to be doubled in size by a matching tract of land in Westmoreland County, which borders the park. But Westmoreland County decided not to participate, instead preferring to use White Oak. The sharing of park facilities is common enough, and other Allegheny County parks such as Harrison Hills and Round Hill routinely serve the populations of adjacent counties.

Renziehausen Park in McKeesport is only a short distance away, and is a popular and fully equipped community park with a band shell and other facilities. Once again, the county park must be understood as an attractive supplement to other, heavily used park facilities.

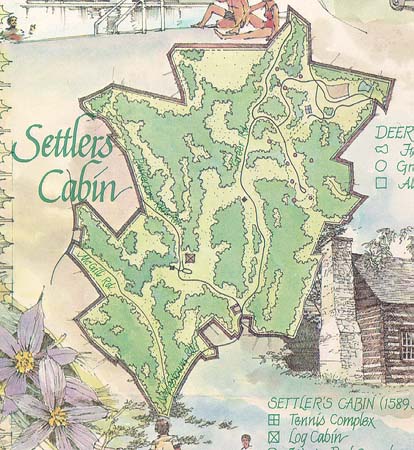

Settler's Cabin

Archaeologists from Carnegie Museum of Natural History helped identify the origins of the 1780 log cabin that gives the park its name. The themes of the 11 groves and shelters are Indian names: Algonquin, Seneca, Apache, Tomahawk.

The region was famous for its high output of shallow coal, and was a maze of abandoned open and back-filled mines when the county secured it. Active wells and exposed oil and gas lines were initial problems, but the grading and reforestation of the land has restored it to rolling wooded slopes and meadows. At 1589 acres, this park was intended to be the largest of the regional parks, and still has a wild, rugged, and unexplored quality not found in the other parks. Located between the Greater Pittsburgh International Airport and Pittsburgh, this large 1589 acre park will see development in the future as population west of Pittsburgh increases.

Settler's Cabin has the most heavily used of the county's three wave pools. The location along the major route to the airport makes it accessible, and swimmers from Ohio and West Virginia can easily reach the site. An impressive diving platform adds to the attraction.

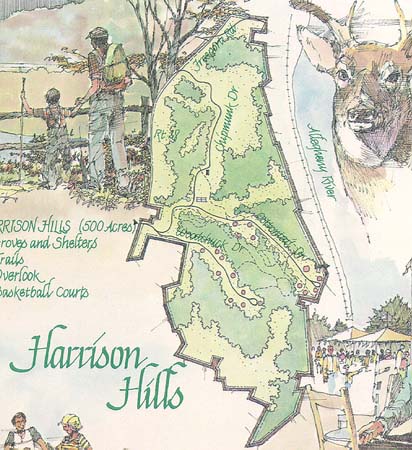

Harrison Hills

Harrison Hills in Harrison township occupies the extreme northeast portion of Allegheny County, bordering the Allegheny River and offering a magnificent overlook in which the viewer can see three other counties--Westmoreland, Butler and Armstrong. The theme of the picnic groves and shelters is seeing birds, trees and plants: Wake Robin, Laurel, Buckeye and Overlook.

There is at an overlook site a memorial to Michael Watts, a lifelong resident of the area who monitored pollution of the river and reported problems to the state environmental agency. When Mike Watts was given, by law, one half of all the fines collected by identifying polluters, he returned his share to the county with the request that they continue his efforts to keep our rivers clean.

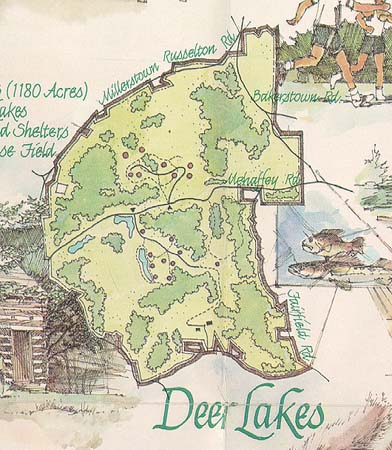

Deer Lakes

This park is a good illustration of the development of natural assets into a specific park idea. Deer Lakes already had a large man-made lake that was used for fishing, and during its development that lake was improved and two other lakes added, all using the same watershed and leading one to the other. The lakes are spring fed, and construction of dams and new settling basins have made the site a paradise for fishermen.

Analysis of the Deer Lakes township area and the service the park could provide to mining communities such as Russelton, Culmerville and Curtisville suggested that fishing was an ideal theme. The state fisheries stock the lakes with pan fish such as bluegill, crappy, perch, sunfish, and trout. Some catfish and a few bass are also found in the lake. Some local residents count on the fish as part of their regular diet. The picnic areas of the park all have the names of fish.

Hartwood Acres

Never intended as one of the original regional parks, Hartwood Acres presented a sudden opportunity for the county in 1969, when the owner of the beautiful Hartwood estate, Mary Flinn Lawrence, then in her last years, offered the property to the county at a very reasonable price providing that development would not take place near her home until after her death. The landscaping alone was worth the purchase price of the property, and the entire estate was a remarkable bargain--an already completed park developed privately with the sorts of resources the county could not duplicate. Hartwood has since become the crown jewel of the county parks system because of its cultural tone and beautiful horse trails.

The manor itself, and the striking stable, have been maintained as the remarkable centerpieces of a public park, which now offers quality entertainment and recreational programs ranging from theater to symphony music and dance. Outdoor sculpture placed throughout the park enhances the artistic theme of Hartwood.

Hartwood now has an outdoor amphitheater on the western side of the property, and the horse trails are still used for riding, in addition to walking. There are no picnic groves or other recreational and sports facilities--this is a park that provides cultural services to people who might not otherwise experience them.

Parks That Never Materialized

It is easy to forget that for every park that comes to fruition there are many park ideas that are proposed, and then die (often timely) deaths. During the Pittsburgh Bicentennial in 1957-58 there was a proposal to put an industrial museum in Schenley Park, and later there was a proposal to build an outdoor theater for the Civic Light Opera near the Schenley Park overlook. In the 1930s there was a plan to construct a performing arts center in South Park. An original idea for an ethnic village in South Park became a plan to build ethnic pavilions in Settler's Cabin Park. The American bicentennial in 1976 triggered many such ethnic heritage programs--but often the funding disappeared before the idea could be realized.

Lack of funding is one reason why a county park development does not occur, but there are others, such as the need to meet space criteria for a public park, or environmental problems. One site in Upper St. Clair township, designated as site number 7 in the original regional parks program, never developed because sufficient land never became available. An initial 200 acres designated for the county park never was supplemented with additional real estate from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, which issued parcels of undeveloped land instead to school districts for ball fields and other facilities. The parcel of land remained too small for county development, and the acreage was finally given to Upper St. Clair township for a community park; the land is still undeveloped.

Linear parks along the rivers, complete with greenbelts, marinas, trails for hiking and biking, have been advocated for a decade, but the actual purchase of the land and the cleanup procedures are still being pursued.

A proposed Ohio River Park on Neville Island never materialized because the land was judged, after initial soil samples proved the property suitable, not be be suitable following a second soil analysis. A study done by the same consultants who studied Love Canal at Niagara Falls, New York, revealed potentially hazardous areas where waste materials had been dumped. As a gesture in the public interest The Hillman Company not only took back the land but reimbursed the county for all expenses incurred in developing the site into a park. Some cleanup has since been undertaken, and many people of Neville Island would like to have the land as a community park.

Serving a Changing Public

Within the last decade the county has built half a dozen soccer fields in its parks to serve a growing interest in that sport. Ten years ago perhaps 4,000 children in the county played soccer; today perhaps 70,000 play it. Much of this expansion was related to the work of an expert organizer who was recruited from England to lay the groundwork for a little league of soccer in the county and went on to work for the city's soccer team, the Spirit, which has now come and gone. But the popularity of the sport will doubtless remain. The continuous care needed to maintain turf on a soccer field--fertilizing, reseeding, top dressing, etc.--is a commitment that the parks administration has made to a growing recreational interest.

Likewise other activities such as cross country skiing, a braille trail and a bicycle moto cross track in North Park, hayrides and sleighrides in Hartwood Acres, ball fields and a nature interpretive center in Boyce Park, lighted basketball courts in several parks--all require constant concern and maintenance. The Allegheny County parks system has a long record of trying to produce appropriate facilities for the public. Sometimes good intentions lead to frustration, as in the natural stone grotto built around a popular spring in North Park, inscribed with the motto "Fountain of Youth" on the archway. When the golf course nearby fixed the leaks in its irrigation system, the Fountain of Youth dried up, but the grotto remains.

Joseph B. Natoli, Director of the Department of Parks, Recreation and Conservation, is confident that the Allegheny County system is as good as any in the country. Such things are hard to prove, but experienced administrators who have seen the competition of of other county parks--how much land they manage, the variety and quality of the services they provide--say that Allegheny County is outstanding.

Six to eight million people use the parks every year; and within the past ten years the number of permanent workers has dropped from about 650 full-time employees to something over 100, through various economies and time-sharing strategies with other county departments. The annual budget is approximately six million dollars, but half of that is returned to the treasury in user fees for certain activities. In addition the real estate benefits to neighboring communities are important. Residences develop near the parks, and the businesses soon follow: stores on the highways, bike rentals, fast food franchises, gas stations, whatever it takes to serve the park-oriented public.

In the geographic hierarchy of park systems--the biggest being the federal land reserves, next down being the rustic, comparatively undeveloped state parks, then the county parks, and finally the more densely populated city parks--the county parks have a special niche. There are enough developed facilities in a county park to make you feel as comfortable as you would in a local community park, and yet the county park has the rural ambience, the sense of outdoors, that you have in a spacious state park. It is a hard task to achieve, to maintain, and to continually improve upon such varied park services over sixty years. The county parks are casually assumed to be a built-in feature of the region's attractive "quality of life," but the story of their evolution, once you see it whole, is a credit to the visionary spirit of many citizens in Allegheny County.

The editor of Carnegie Magazine R. Jay Gangewere has written about Schenley Park and Highland Park in previous issues of the magazine. His research for this article included bicycling, strolling, swimming and picnicking in the county parks during the course of a year and a half.

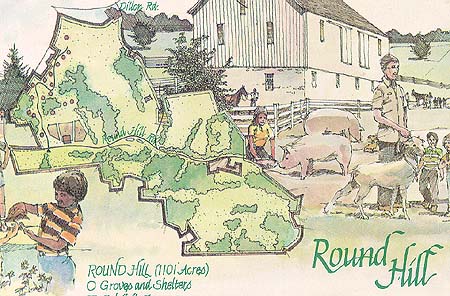

The park maps shown on this website are part of the fold-out map, developed by Carnegie Magazine, the publication of Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, as a supplement to "The Allegheny County Parks." The Allegheny County Department of Parks, Recreation and Conservation provided information for the park maps and the magazine article. © Carnegie Magazine

R. Jay Gangewere, Editor.

Edward Dumont, Artist.

Jeffrey Boyd, Designer.Entered online 8 February 2000.

|

Return to Pa Pitt's Master Index |